Sepsis

A 5-year-old male presents to the emergency department with fever, respiratory distress, and altered mental status.

History

The patient was noted to have upper respiratory viral symptoms – cough, congestion, and rhinorrhea – beginning approximately 7 days ago. Over the last two days, he developed high fevers up to 104°F (40°C), which required alternating doses of acetaminophen and ibuprofen at home. Overnight, his parents noted increased work of breathing and difficulty arousing him from sleep, prompting presentation to the emergency department.

Key Physical Exam

Vitals: T 39.5°C, HR 140 bpm, RR 35/min, BP 80/45 mmHg, SpO₂ 94% on room air

General: Ill-appearing, sleepy but arousable to voice

HEENT: Mucous membranes dry, neck supple with full range of motion, oropharynx clear

Lungs: Focally diminished aeration and crackles over the right lower and middle lung fields. Tachypnea without accessory muscle use

Cardiovascular: Tachycardic, regular rhythm. Normal S1 and S2. No murmurs. Strong distal pulses but 3 second capillary refill

Abdomen: Soft, nontender and nondistended, normal bowel sounds

Neurologic: Arouses to voice but remains asleep during remainder of the exam, moving all extremities equally when awake without any focal deficits. PERRL, EOMI without nystagmus

Skin: No rash or petechiae, hands and feet are cool to the touch

- Pneumonia – this patient has focal findings on his lung exam, lower limit of normal oxygen saturation, and tachypnea. He also had a recent upper respiratory infection (URI) with progressive fever and respiratory distress over the last two days, indicative of viral URI with secondary bacterial pneumonia.

- Sepsis/Septic Shock – though pneumonia is the most likely focal source of infection for this patient, he now appears to have multi-system involvement and has developed critical illness. His vital signs are notable for fever, tachycardia, and tachypnea which prompt concern. His exam is also concerning for signs of impaired end-organ perfusion given his altered mental status and delayed capillary refill.

- Meningitis – given his altered mental status, fever, and signs of systemic illness, meningitis should remain on the differential. Like pneumonia, this could be another focal source of infection. He has no characteristic neck rigidity, headache, or potential skin findings.

- Other causes of altered mental status (AMS) including electrolyte/metabolic derangement or toxic ingestion which are less likely given constellation of symptoms but should remain on the differential and considered if initial testing is unrevealing.

Though the primary cause of shock can be mixed and multifactorial, there are four broad classifications: hypovolemic, distributive, cardiogenic, and obstructive. Classifying shock in this way can help identify potential causes and highlight immediate areas for intervention. Below we classify shock into its various causes:

- Hypovolemic Shock: this is the most common cause of shock in children resulting from decreased preload as a result of intravascular fluid depletion. This results in reduced stroke volume and cardiac output with compensatory increased systemic vascular resistance. Common causes include GI losses from vomiting and diarrhea, insensible losses from fever, or inadequate intake.

- Distributive Shock: results from decrease in systemic vascular resistance and associated peripheral vasodilation. This includes:

- Septic Shock: due to dysregulated host response to infection.

- Anaphylactic Shock: due to severe IgE mediated hypersensitivity reaction to antigen.

- Neurogenic Shock: due to trauma to the spinal cord or brain resulting in loss of sympathetic venous tone.

- Cardiogenic Shock: results from intracardiac causes leading to reduced cardiac output (i.e.. pump failure). Causes include:

- Cardiomyopathy: in pediatrics this includes familial, infectious, or idiopathic cardiomyopathy.

- Arrhythmia: both atrial and ventricular arrhythmias can cause cardiogenic shock.

- Mechanical: severe valvular insufficiency.

- Obstructive Shock: results from obstruction to blood flow impairing cardiac output. Causes include cardiac tamponade, tension pneumothorax, and massive pulmonary embolism.

Evaluation and Management

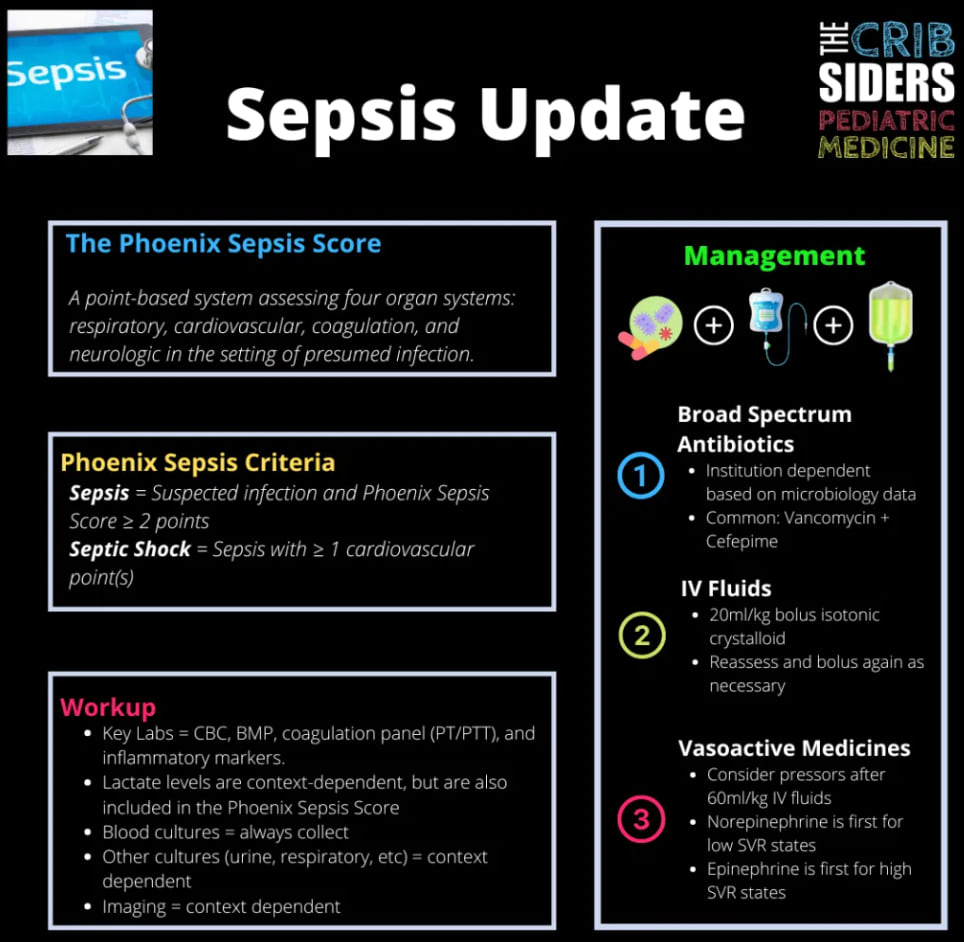

Prompt recognition and clinician suspicion for sepsis is crucial in enacting rapid evaluation and initial steps in management prior to further decompensation. In this case, the leading differential is superimposed pneumonia with progression to septic shock. It is important to evaluate signs of end-organ perfusion, obtain necessary cultures to identify the corresponding microbe, and begin resuscitation with broad spectrum antibiotics and support of hemodynamics.

Initial Evaluation

- Laboratory evaluation:

-

- CBC to evaluate WBC count for leukocytosis, bandemia (elevated level of immature white blood cells, a sign of infection/inflammation), and potential thrombocytopenia associated with critical illness.

-

- CMP to assess electrolytes, and end-organ perfusion including renal function (BUN/Cr), LFTs for hepatic involvement.

-

- Inflammatory markers with CRP and Procalcitonin.

-

- VBG with lactate to assess for acidosis and lactatemia.

-

- Point of care blood glucose to assess for hypoglycemia.

-

- Coagulation studies including PT, PTT, INR to assess for concurrent coagulopathy in the setting of critical illness.

- Microbiology:

-

- Obtain blood culture prior to antibiotic administration if possible.

-

- Obtain urinalysis and urine culture and consider obtaining viral testing.

-

- If safe, consider lumbar puncture to obtain CSF culture.

- Imaging:

-

- Obtain 2-view Chest X-ray to assess for pneumonia.

-

- Consider emergent head imaging (such as CT head without contrast) given altered mental status to rule out bleed or other intracranial process.

Management:

- Obtain intravenous (IV) access.

- Given tachycardia and hypotension, should support hemodynamics at this time. Begin with a 20mL/kg isotonic crystalloid fluid bolus (normal saline or lactated ringers). Reassess perfusion and consider giving a total of 20-60mL/kg of fluid bolus. If hypotension is persistent after crystalloid resuscitation, vasoactive agents (i.e. epinephrine continuous infusion) would be the next step in management.

- Begin prompt broad-spectrum antibiotics. In this case, we would likely begin Cefepime and Vancomycin for broad coverage of gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria including MRSA.

- Frequent assessment of mental status, perfusion, blood pressure monitoring, and urine output monitoring.

- Maintain a low threshold to suspect and initiate workup for sepsis in any child with systemic signs of illness.

Early signs such as fever, tachycardia, altered mental status, and delayed capillary refill may be subtle but indicate evolving critical illness. Prompt recognition enables early intervention before progression to decompensated shock. - Prioritize early assessment for end-organ dysfunction and blood, urine, or CSF cultures to guide antimicrobial management.

Along with clinical signs of sepsis, it is important to obtain a thorough laboratory work up screening for multi-system involvement including hepatic and renal impairment as well as obtaining a prompt blood culture before empiric antibiotic administration if possible. However, obtaining blood, urine, or CSF cultures should not delay antibiotic treatment – for a critically ill child, antibiotics might be life-saving – in certain cases it is appropriate to treat first, figure out where the infection is later. - Immediate crystalloid resuscitation and empiric broad-spectrum antibiotics are cornerstone therapies.

Timely administration of 20-60 mL/kg isotonic fluids and empiric broad-spectrum antibiotics improves outcomes and is crucial in preventing progression of septic shock. Always reassess the patient after each bolus, with careful attention to ensure the patient is not developing signs of fluid overload (i.e. new respiratory distress, crackles, or desaturations could indicate pulmonary edema)

Click the drop down to reveal the correct answers

Q1. True or False: Anaphylactic shock always presents with cutaneous findings such as urticaria or angioedema.

Q2. True or False: All patients can be discharged right after a dose of intramuscular epinephrine since there is no risk for recurrence of symptoms.

Q3. How does administration of intramuscular epinephrine treat anaphylactic shock?

- Vasoconstrictor effects decrease upper airway mucosal edema.

- Alpha- and beta-adrenergic agonist activity increases vascular tone to reverse hypotension.

- Beta-1 adrenergic stimulation increases inotropy and chronotropy.

- Beta-2 adrenergic stimulation cases bronchodilation.

- All of the above.

False. As many as 10% of patients present without cutaneous findings and often have more severe symptoms.

False. Up to 20% of patients have a biphasic reaction and observation time in the emergency department depends on patient risk factors for such reaction.

E. Epinephrine is the medication of choice and first line treatment of anaphylaxis. The mechanism of action includes adrenergic stimulation to decrease airway edema, cause bronchodilation, increase cardiac output by increasing heart rate and vascular tone.

- UpToDate: Children with sepsis in resource-abundant settings: Rapid recognition and initial resuscitation (first hour).

Children with sepsis in resource-abundant settings: Rapid recognition and initial resuscitation (first hour) - UpToDate - StatPearls: Septic Shock. Septic Shock - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf

- PEM Playbook: From the Ashes of SIRS: The Phoenix Sepsis Score.

https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/from-the-ashes-of-sirs-the-phoenix-sepsis-score/id1035668219?i=1000657488456 - PedsCases - Sepsis, Septic Shock