CGH Spotlight

The Spotlight is a way for us to highlight the work from our Partnerships, Programs, and Scholars. Please find our most recent article below:

NOVEMBER 2025

Stephen Avery, PhD, FAAPM recently advanced cancer equity efforts in Ghana through high-level global financing discussions at the United Nations and community awareness engagement at the BCI “Walk for the Cure,” Ghana’s largest breast cancer event. Amid rising breast cancer rates and late diagnoses in Ghana, Avery emphasized the importance of early detection, training, and strong international partnerships. His work, supported by new NIH funding, highlights Penn’s growing leadership in global education, innovation, and collaboration in cancer care.

Stephen Avery, PhD, FAAPM recently advanced cancer equity efforts in Ghana through high-level global financing discussions at the United Nations and community awareness engagement at the BCI “Walk for the Cure,” Ghana’s largest breast cancer event. Amid rising breast cancer rates and late diagnoses in Ghana, Avery emphasized the importance of early detection, training, and strong international partnerships. His work, supported by new NIH funding, highlights Penn’s growing leadership in global education, innovation, and collaboration in cancer care.

During a pivotal season for global health diplomacy and cancer advocacy, Dr. Stephen Avery, Professor of Radiation Oncology and Director of Global Radiation Physics and GEF recipient, has continued to bridge continents in the fight against cancer. His recent engagements—from the United Nations to the streets of Kumasi—reflect Penn Medicine’s growing leadership in global oncology and equitable access to care.

During a pivotal season for global health diplomacy and cancer advocacy, Dr. Stephen Avery, Professor of Radiation Oncology and Director of Global Radiation Physics and GEF recipient, has continued to bridge continents in the fight against cancer. His recent engagements—from the United Nations to the streets of Kumasi—reflect Penn Medicine’s growing leadership in global oncology and equitable access to care.

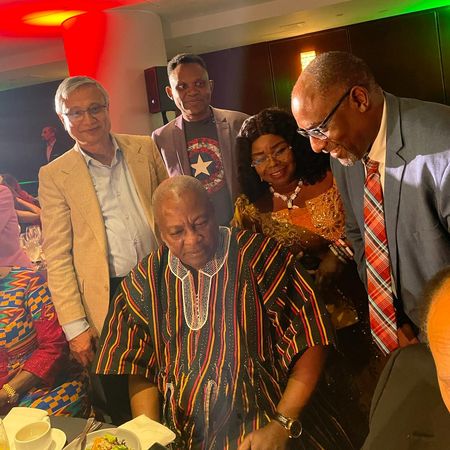

In September 2025, during the United Nations General Assembly Week, Dr. Avery participated in the High-Level Convening on Redefining Global Cancer Financing, hosted by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and Bloomberg Philanthropies in New York City. The meeting convened heads of state, global health leaders, and cancer experts to design sustainable funding models that expand cancer care across low- and middle-income countries.

Alongside his Penn colleague Dr. Surbhi Grover, Co-Director of the Center for Global Oncology, Dr. Avery underscored Penn’s commitment to advancing global equity in cancer treatment. Following the session, he met with His Excellency John Dramani Mahama, President of Ghana,(pictured to discuss expanding collaborations in cancer research, training, and infrastructure development—a conversation signaling Ghana’s growing role as a regional hub for oncology innovation.

Just weeks later, on October 4, Dr. Avery joined thousands of participants in Kumasi, Ghana, for the Breast Care International (BCI) Walk for the Cure, the nation’s largest breast cancer awareness event. Joined by AAPM President-Elect Dr. Andrew Maidment, Avery addressed over 30,000 attendees—from survivors and clinicians to students and local leaders—who marched under the theme “A Cure Worth Fighting For.”

In his remarks, Dr. Avery emphasized that “cancer awareness is the first step toward equity,” highlighting the power of education and early detection to save lives. His participation reinforced Penn’s long-standing collaboration with BCI Ghana and the American Association of Physicists in Medicine (AAPM) to strengthen cancer care infrastructure across Africa.

Breast cancer remains the most frequently diagnosed cancer and the leading cause of cancer death among Ghanaian women. According to the World Health Organization, breast cancer accounts for roughly 18% of all new cancer cases in Ghana, with over 4,400 new diagnoses annually. Late presentation is a critical challenge—more than 70% of cases are detected at advanced stages, when treatment options are limited and outcomes are poor.

Events like the Walk for the Cure play a vital role in shifting this narrative. By promoting early screening, public education, and reducing stigma, Ghanaian advocates like BCI—supported by global partners such as Penn—are helping women access lifesaving care earlier and with greater dignity.

Dr. Avery’s global impact extends beyond advocacy. In September 2025, he was awarded two new NIH grants totaling $2 million to advance innovation, education, and equity in radiation oncology.

The first, a $1.5 million NIH R25 Research Education Grant, funds AMPERE (Access for Medical Physicists to Education and Research Excellence)—a pioneering program using AI and virtual reality to train the next generation of medical physicists in 11 countries across Africa, Asia, and Latin America. The second, a $0.5 million NIH R01 subaward, supports research into Spot Scanning Arc (SPArc) Proton Therapy, a next-generation framework designed to enhance precision and efficiency in radiation treatment.

The first, a $1.5 million NIH R25 Research Education Grant, funds AMPERE (Access for Medical Physicists to Education and Research Excellence)—a pioneering program using AI and virtual reality to train the next generation of medical physicists in 11 countries across Africa, Asia, and Latin America. The second, a $0.5 million NIH R01 subaward, supports research into Spot Scanning Arc (SPArc) Proton Therapy, a next-generation framework designed to enhance precision and efficiency in radiation treatment.

From the halls of the United Nations to the vibrant streets of Kumasi, Dr. Stephen Avery’s work exemplifies the synergy between innovation, education, and compassion. His efforts—anchored in Penn’s mission to promote global health equity—remind us that advancing cancer care is not only a scientific endeavor but a shared human responsibility. In Ghana and beyond, that commitment is translating into real progress—and hope.

PAST SPOTLIGHTS

Dr. Farouk Dako is a radiologist and global health researcher whose work focuses on expanding access to cancer imaging and equitable care in low-resource settings. He leads collaborative initiatives across Africa and recently assumed the role of Director of the Botswana-UPenn Partnership, where he is advancing training, research, and clinical capacity to address both infectious and non-communicable diseases.

Dr. Farouk Dako is a radiologist and global health researcher whose work focuses on expanding access to cancer imaging and equitable care in low-resource settings. He leads collaborative initiatives across Africa and recently assumed the role of Director of the Botswana-UPenn Partnership, where he is advancing training, research, and clinical capacity to address both infectious and non-communicable diseases.

Let’s start at the beginning — what initially sparked your interest in global health and health equity? Was there a pivotal experience or influence that set you on this path?

Growing up in Nigeria, there was a wide economic gap between the haves and the have-nots that was visible to anyone who could see. There was also a social expectation for everyone to participate in uplifting of individuals in vulnerable situations and very little held hope for government intervention. We had everyday vivid scenarios of social determinants of health at play.

You’ve trained and worked across multiple continents. How has your personal and professional background shaped your perspective on disparities in cancer care and imaging access?

Meeting with and listening to folks of different backgrounds and realities has left me with the feeling that our underlying humanity and drive to live connects us all. Providing opportunities for good health provides the most fundamental opportunity to fulfil one’s human potential.

Your work has focused on improving imaging and cancer care in low-resource settings, including Nigeria and Botswana. Can you talk about one or two projects that have been especially meaningful or impactful to you?

Leading and participating in efforts to include medical imaging data from African countries in pivotal projects published in major journals including Nature Communications and Radiology: Artificial Intelligence is something that comes to mind as demonstrating this possibility is important to set news standards for inclusive data science efforts. I’m also proud of leading efforts to implement imaging informatics and artificial intelligence solutions in Africa with RAD-AID International and providing guidance for others to do the same through scientific writing and informal consultations. The most enjoyable part of my work is collaborating with individuals who are smarter than me.

You co-founded the Penn Global Health Imaging Case Competition — what inspired the creation of this initiative, and what were your goals for it when it began?

This exciting competition, a collaboration with CHOP and CGH, is focused on giving trainees in low- and middle-income countries a platform and incentives to engage in scientific writing, presenting and networking. I found the incentive for such activities to be severely lacking and yet of extreme importance in training the next generation of healthcare professionals and scientists. Part of the goal is for trainees to develop the habit of saving and disseminating interesting medical knowledge that they encounter daily.

This competition brings together students and early-career professionals from around the world. How do you think programs like this can help build the future workforce in global oncology?

Programs like the case competition and many others provide opportunities for networking, collaboration, innovation and continuous learning which is critical, particularly in environments with disinvested educational and healthcare systems. Most importantly, I think they could give trainees the belief that they could be part of the global academic and scientific community which often feels like a far reach to some. There is a need for more longitudinal training programs targeted to fit the needs of the local audience.

Congratulations on your appointment as Director of the Botswana-UPenn Partnership. What does this role mean to you personally and professionally?

I’m still processing what it means as I settle into Botswana with my family. The history and scale of the BUP operations is something that we should be proud of as it represents Penn’s flagship global health program. The potential to improve healthcare in Botswana and beyond is immense - particularly in the current funding climate. I’m truly humbled to be able to help strengthen the program and very much looking forward to learning from colleagues in Botswana, Philadelphia and beyond. I’m grateful for all prior experiences and mentors as I think they have prepared me to meet this moment.

The Partnership has a rich history of collaboration in HIV research and training. Where do you see the greatest opportunities for growth in the next phase of the partnership?

Easy- Data Science, Digital Health and Artificial Intelligence

How do you plan to balance the priorities of sustaining long-term clinical and research collaborations while also exploring new areas such as non-communicable diseases, including cancer?

We can leverage prior and existing projects to introduce new concepts. For example, using existing Tuberculosis infrastructure to investigate Lung cancer. Thankfully we have some of the best researchers in the world working through BUP who can evolve their science to meet current and future needs. Working on solutions for health systems strengthening that are not siloed in particular diseases is an approach that would result in improved over health outcomes.

You’ve been deeply involved in mentoring students and trainees. What role does mentorship play in sustaining global health partnerships, and how do you plan to expand those opportunities through your new position?

Mentoring students is a critical component of our mission. They represent the future that we have the opportunity to shape. We will try to instill a deep sense of cultural humility and curiosity in every student that engages with BUP through various activities including collaboration with local peers and teams and intentional exposure to local customs and local solutions.

What’s next for you — are there any upcoming initiatives or research directions you’re especially excited about in the coming year?

I’m excited to first work on improving the connectivity within our BUP teams and visibility of people and work being done. I’m thrilled about all the new projects that have been recently awarded to be started at BUP. Stay tuned for more exciting updates!

Dr. Megan Rybarczyk is leading the expansion of global emergency medicine at Penn through the creation of the Penn Global Emergency Medicine Fellowship and the launch of the inaugural Global Emergency Medicine Case Competition. These initiatives provide structured training, mentorship, and opportunities for medical trainees to address complex global health challenges in emergency care. Her work underscores the vital role of departmental support in building sustainable, trainee-focused programs that strengthen Penn’s impact on global health systems and prepare the next generation of globally engaged emergency physicians.

Dr. Megan Rybarczyk is leading the expansion of global emergency medicine at Penn through the creation of the Penn Global Emergency Medicine Fellowship and the launch of the inaugural Global Emergency Medicine Case Competition. These initiatives provide structured training, mentorship, and opportunities for medical trainees to address complex global health challenges in emergency care. Her work underscores the vital role of departmental support in building sustainable, trainee-focused programs that strengthen Penn’s impact on global health systems and prepare the next generation of globally engaged emergency physicians.

What initially inspired your interest in global emergency medicine?

I have been interested in medicine for as long as I can remember. As I started exploring different medical careers, I found I was most passionate about Emergency Medicine (EM), given both the diagnostic and procedural aspects to the specialty as well as the opportunity to care for individuals in all circumstances and at every stage in life. Global EM allows me to expand that opportunity, as well as the resulting impact, even more.

How has your experience working in resource-denied settings shaped your approach as both a clinician and educator here at Penn?

Working in resource-denied settings not only helps to personally improve your skills as a clinician (1) and educator, but also leads to expanded networks, exchange of ideas, and systematic improvement. It allows you to learn different techniques and approaches and to bring them to your setting as well as to share your experience in other settings.

(1) - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35572845/

What motivated the creation of the Penn Global Emergency Medicine Fellowship? How did you go about designing its structure and curriculum?

Global Health is an essential part of today’s medical education, and my goal was to bring that to the Department of EM through a fellowship. As a result of my activities with the fellowship, I also advise other faculty on Global EM work as well as residents and students interested in rotations and projects. When designing the curriculum, I drew from my own experience as a fellow and from existing models of fellowships offered across the country in my experience in being involved with and leading the Global EM Fellowship Consortium (GEMFC) – the national organization for all Global EM Fellowships.

What gaps in training or career development were you aiming to address with this fellowship?

There are many facets of Global Emergency Care – education, research, humanitarian/disaster response, and so on. In my opinion, the greatest impact can be made through a focus on systems development through education and training, so that is where our fellowship is focused. All training programs are currently in need of more of a focus on Global Health – and on Global Emergency Care, in particular – so the fellowship focuses on developing leaders in that space who will expand this programming at Penn and elsewhere.

Can you share an early success story or milestone from the program that you're particularly proud of?

All of our fellow graduates to date have gone on to academic positions in Global EM. They are expanding the work they started in fellowship, bringing Global EM education to other programs, and “paying it forward”.

Congratulations on the inaugural Global Emergency Medicine Case Competition! What were the most important lessons or insights you gained from this first event?

Thank you! What a fantastic event. The credit really goes to the Department of Radiology (and partners) in being the pioneers in this type of event as well as the Center for Global Health for all of the assistance and support for the first Global EM Case Competition. It is always amazing to hear about interesting cases from around the world and to be inspired by the work of others in this field – particularly those who are most often doing it under more challenging circumstances and in many areas of the world where the specialty is not even recognized yet! We hope to continue and expand this initiative to provide a platform for learning, networking, and collaboration, and for advocacy for the specialty worldwide.

From your experience, what are the most important elements of institutional buy-in when building new global health programs?

As mentioned, Global Health should be an integral part of training today. It (selfishly) improves care locally as well as contributes to improved healthcare globally. It takes working with leadership and presenting the evidence to discuss how even relatively small up front and ongoing investment can pay huge dividends in terms of not only improved training locally, but also enhance recruitment, increase learner and faculty well-being, and elevate the institutional standing nationally and internationally.

What are your hopes for the future of global emergency medicine at Penn and beyond?

I hope to continue to expand the Global EM Section within our department as well as to assist with the expansion of Global Health programming and opportunities across the institution. I am always looking to start new partnerships and collaborations. Beyond Penn, I plan to continue to advocate for training in and resources for Global Emergency Care – we know that potentially half of all deaths in resource-denied settings might be avoided with the implementation of effective and efficient emergency care systems, so there is a lot of work to do!

Penn's Center for Global Oncology (CGO) is advancing cancer care in low- and middle-income countries through global partnerships, faculty-led initiatives, and cross-continental education. Led by CGH Scholars, Dr. Lawrence Shulman and Dr. Surbhi Grover, the CGO empowers Penn faculty and trainees to engage in research, training, and system-strengthening efforts in countries like Botswana, Rwanda, and Tanzania—helping shape a more equitable future for global cancer care.

Penn's Center for Global Oncology (CGO) is advancing cancer care in low- and middle-income countries through global partnerships, faculty-led initiatives, and cross-continental education. Led by CGH Scholars, Dr. Lawrence Shulman and Dr. Surbhi Grover, the CGO empowers Penn faculty and trainees to engage in research, training, and system-strengthening efforts in countries like Botswana, Rwanda, and Tanzania—helping shape a more equitable future for global cancer care.

What was the original vision behind creating the Center for Global Oncology, and how does it build on your previous work?

Dr. Shulman: Before joining Penn in 2015, I founded the Center for Global Cancer Medicine at Dana-Farber and helped establish cancer programs in Rwanda and Haiti with Partners In Health (PIH). At Penn, I saw a strong interest in global oncology and sought to continue that work by engaging faculty, trainees, and students in meaningful international partnerships. Establishing the Center for Global Oncology was a key part of my recruitment.

Dr. Grover: Training the next generation of experts is critical. One of CGO’s central pillars is to support junior faculty, trainees, and students in building careers in global oncology. We’ve drawn on past collaborations—both nationally and internationally—to develop sustainable, high-impact initiatives through the Center.

What are the most pressing gaps in cancer care in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), and how does CGO aim to address these gaps?

Dr. Grover: One of the greatest challenges in LMICs is the lack of trained human resources, effective healthcare leadership, and sustainable financing. These issues affect every stage of cancer care—from diagnosis to long-term treatment. At CGO, we support faculty-led training programs that build local capacity and empower future leaders. We also work closely with leadership in partner countries to shape national cancer care strategies. Additionally, we collaborate with international organizations like the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) to expand access to training and global expertise.

Dr. Shulman: Quality cancer care cannot exist without a strong healthcare foundation. Programs in low-income settings have consistently failed when implemented without robust infrastructure. At CGO, we follow the “5 S’s” model—Staff, Stuff, Space, Systems, and Social Support—to guide our efforts. Cancer care must include not only trained physicians and nurses but also pathology, radiology, lab services, and essential social support for patients. I believe research should follow healthcare strengthening—not precede it.

You’ve spoken about the importance of local leadership. How does CGO ensure that its global oncology programs are co-developed and co-led by partners in LMICs?

Dr. Grover: Strong partnerships are built on mutual respect, shared priorities, and deep cultural understanding. We work closely with our LMIC partners, allowing them to lead in identifying critical needs and helping shape and scale programs. Respecting local context is essential to every initiative we undertake.

Dr. Shulman: We view ourselves as guests in the countries where we work. We go only where invited, and our in-country colleagues lead the efforts. We describe our model as “accompaniment,” not ownership. Building mutual trust requires long-term commitment. Our partners must know that we are invested in their success for the long haul.

Dr. Grover: These values are foundational to CGO. Every program we build reflects shared priorities and is rooted in equitable, context-specific collaboration between Penn and our global partners.

CGO recently launched a Grant Program to support faculty-led initiatives in LMICs. Why is this kind of internal funding so important now, given the uncertain global health funding landscape?

Dr. Shulman: Funding global cancer programs has always been difficult—and it’s even more challenging today. Federal grants are increasingly at risk. Programs like USAID and PEPFAR have supported our work but are facing cuts. Much of our work in Rwanda, Haiti, and now Lesotho is funded through philanthropy, including support from Partners In Health and foundations like the Breast Cancer Research Foundation. With strong backing from faculty and alumni, Penn can help bridge these gaps.

Dr. Grover: These internal grants are vital. They provide seed funding for faculty to launch or expand partnerships, especially when external funding is delayed or unavailable. Supporting these early efforts ensures our faculty are well-positioned for larger grants and long-term impact.

What does success look like for the Center for Global Oncology five years from now—and how will we measure its impact?

Dr. Grover: In the next five to ten years, I see CGO playing a leading role in transforming how cancer care is delivered in LMICs. Our priority is to train future leaders in global oncology and expand Penn’s participation in national and international collaborations. By developing large-scale, high-impact programs, we hope to drive sustainable improvements in cancer care equity worldwide.

Dr. Shulman: As my colleague Dr. Cyprien Shyirambere said, the ultimate measure of success is patient survival. If we’re not improving outcomes, we’re falling short. To get there, we must address every link in the value chain of care—access, affordability, diagnostics, treatment, and follow-up. Implementation science will continue to guide our work, identifying where we’re making progress and where new strategies are needed.

Dr. Robert Gross is the 2025 recipient of the Lewinter-Suskind Faculty Award in Global Health. He is a global leader in HIV research and a dedicated mentor to students and trainees at Penn and abroad. His work through the Botswana-UPenn Partnership has advanced equitable, collaborative research and local capacity building. In this interview, he shares reflections on mentorship, sustainability, and navigating shifting global health priorities. We are proud to feature Dr. Gross in the April 2025 CGH Spotlight.

Dr. Robert Gross is the 2025 recipient of the Lewinter-Suskind Faculty Award in Global Health. He is a global leader in HIV research and a dedicated mentor to students and trainees at Penn and abroad. His work through the Botswana-UPenn Partnership has advanced equitable, collaborative research and local capacity building. In this interview, he shares reflections on mentorship, sustainability, and navigating shifting global health priorities. We are proud to feature Dr. Gross in the April 2025 CGH Spotlight.

Congratulations on receiving the 2025 Lewinter-Suskind Global Health Faculty Award! This year’s award focuses on mentorship and the promotion of sustained global health careers. You’ve had a long career as an infectious disease clinician and researcher. What initially sparked your interest in studying infectious disease outside of the USA?

Multiple reasons: 1) As an epidemiologist, I follow “Sutton’s law.” When asked why he robbed banks, Willie Sutton answered “Because that’s where the money is.” For an HIV clinical epidemiologist wanting to answer population-based questions, the numbers of people with HIV needed to enroll in studies are often larger than feasible in the US. Yet, the results often have important implications for people with HIV in the US. This is one important way international research benefits Americans. I looked to partner with countries where there is a higher concentration of people affected than here in the US and Botswana had already established a relationship with Penn (the Botswana-UPenn Partnership) making it a natural place for me to expand my program. 2) Living in southern Africa during medical school, I fell in love with the region and felt a strong connection to the people, which drove me to wanting to help stem what was an out of control HIV epidemic in the early 2000s. 3) I recognized that helping answer important questions in a place like Botswana was a way to advance America’s standing in the world, prevent dire circumstances in distant places from becoming bigger financial and perhaps, military burdens on the US. I therefore felt that focusing my attention on a place so heavily affected by HIV would ultimately yield dividends for Botswana, but also to the US. And I believe it has been beneficial for both countries.

You’ve mentored a wide range of trainees from both Penn and global partner institutions. How do you approach mentoring across cultures, disciplines, and experience levels?

In short, I don’t distinguish mentoring by culture or discipline. I mostly mentor clinically trained individuals to learn the new skills of clinical epidemiology to apply to their existing knowledge base. So, the only characteristics I take into account in adjusting my approach to mentees relate to personal style: does the trainee hold onto ideas too long and abandon “risky” projects too soon and need to be pushed to stay with an idea longer or do they want to go in so many directions at once that they need to be channeled in the most promising directions? Do they need more help in managing budgets or personnel? Do they need more input on time management or writing style? So, in essence, I tailor the type of feedback to the areas of weakness that might hold mentees back from achieving their goals irrespective of their cultural background.

Maintaining your impressive domestically focused responsibilities while pursuing global opportunities sounds daunting. How do you make this work?

Efficient time management and excellent staff. I was an early adopter of video conferences, well before the pandemic made it routine. But I bristle when people critique international researchers living in the US whom they accuse of managing by “remote control.” As if! Remote-yes-I live 6 time zones west of Botswana. But I have made these distant projects work by deeply learning the local environment (i.e., the culture of doing business), made strong connections by being a partner who says what he’s hoping to do and then following through, and by carefully vetting and hiring staff whose mission is aligned with mine, and who expect excellence from themselves. And importantly, I keep open lines of communication and am transparent with how I manage budgets. I am also a big proponent of giving the staff the autonomy to make decisions within their skill set and purview and reward good performance with praise, small personal gifts, and sincere appreciation. It’s actually not different than my domestic management approach. The only real differences are getting up early some mornings to make early afternoon (Central Africa Time) meetings and carving out the time to go to Botswana for a week or two a few times a year. And when I’m there, making sure I have good wifi so I can manage my projects virtually back in the US!

How do you ensure that your work with international collaborators promotes local leadership and long-term impact?

I keep in mind the phrase leaders in Botswana have expressed to me over the years: “Prof, you’ll know you have been successful in our eyes if you train Batswana (Botswana citizens) to replace you.” My initial reaction was “But I want to keep having a role here!” And their response was: “We do too, it will just be a different (more senior) role!” I trust they’ll keep their word to keep inviting me to work there even as my trainees take over the projects I would have run earlier in my career. It is important to remind yourself that you’re a guest in the country and that your career wouldn’t be anything near what it is if you weren’t welcomed and supported there. It keeps you humble and keeps you wanting to be a fair partner who remains valued.

Cultural humility is often cited as essential in global health, but it can be difficult to define in practice. How do you approach this in your work, and how has it influenced your relationships with local partners and communities?

I think cultural humility is essential for a clinician and researcher, but it goes way beyond global health. There are many stakeholders in our research and training enterprises even in Philly. For example, as Co-Director of the Penn Center for AIDS Research, we serve as a research arm the Department of HIV Health of the City of Philadelphia directed by my colleague Kathleen Brady MD MSCE (Penn GME 2002). She and her colleagues have perspective on issues affecting people with HIV that I lack as an investigator studying the continuum of HIV care. I recognized early on in all of my research relationships that paying attention to what everyone brings to the table leads to a richer research environment and avoids both management and scientific pitfalls. The culture at a department of health is to maximize the health of the population, whether here or in Botswana. The culture of academics is to answer key questions. Those two cultures heavily overlap, but do not map perfectly onto each other. In order for me to get research grants, the lifeblood of the academic, I need a convincing argument that the science is worth pursuing. At the same time, in order to be supported to work in Botswana (and Philly), I need a convincing argument that the research answers will be relevant to the public. Enter cultural humility. Unless you understand what is desired by all stakeholders (funders, peer academics, local constituents) in these settings, you end up with an incomplete picture and risk failure and loss of trust. Perhaps Botswana being a foreign country adds a small added wrinkle but the fundamental issues apply everywhere.

Can you recall a time when your understanding—or misunderstanding—of local customs, values, or language had a major impact on a project or partnership? What did you take away from that experience?

I was starting a smoking cessation project in Botswana and hired staff to implement a behavioral counseling strategy with smokers with HIV. There are large numbers of people with HIV who want to quit smoking in Botswana (see “Sutton’s law” above) but had no access to interventions of any kind. I was expecting to be flooded with enrollees. After three weeks of no one enrolling, I had the team role play the “pitch” to me as a mock prospective trial participant. They proceeded to sternly scold me for being a smoker, which they soon realized from my disappointed reaction that I was obviously turned off to the project and would have opted out. With a little coaching, the team pivoted to a warm, sympathetic, accepting approach to people who were struggling with addiction. Within a few weeks, they enrolled 40 participants. These results led directly to the Thotloetso (“Encouragement”) Trial ultimately being funded by NIH and this month completed enrollment of 650 smokers with HIV. This episode highlighted for me the corrosive nature of judgementalism in medicine but also the ability of people of all cultures to adapt and change. While judgementalism can be particularly oppressive in other countries, it is something I think we struggle with in the US as well and I am hoping to work to address it in future research.

Looking ahead, what areas of global health research or mentorship excite you most? Are there new directions or partnerships you hope to pursue in the coming years?

I have been very proud to have trained several Batswana in HIV clinical epidemiology, many obtaining the MSCE, the same degree I hold from Penn. But I think further advanced training is necessary for them to achieve their ultimate goal of research independence. The advantage I had being an American was having access to an NIH training grant mechanism that allows us to spend large blocks of time on research for the years it takes to mature toward independence. Foreigners cannot access these NIH grants and they get bogged down in clinical and administrative obligations that pay their salaries. As my next training mission, I would like to obtain funding from the Fogarty International Center or similar agency to support those MSCE (and equivalently trained) Batswana to have protected time from their teaching and clinical obligations to pursue methodologically rigorous clinical research answering key questions for the Botswana setting. A US-based model is the K12, where the PI of the training grant assigns trainees to slots for salary support that would allow them to pursue independent research. As for mentoring the trainees, many of my senior colleagues would love the opportunity to get deeply involved in Botswana by (remotely) mentoring these individuals similar to the way we mentor K awardees in the US. The expected outcome would be that the supported research would lead to pilot data for independent research grants from Wellcome Trust, NIH, and other mechanisms for the mentees to conduct impactful research. That would be the natural next step in training Batswana to replace me.

Considering recent challenges to federal support for HIV research, how do you see shifts in funding landscapes affecting global health work, and what strategies have you found effective in sustaining international research and mentorship efforts during uncertain times?

The dire threat to HIV and other global research cannot be overstated. The US has been rightly praised for its support of this work over the past 2+ decades. The yield on the investment has been incredible. Just in HIV alone, 26 million lives have been saved by the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). This has been terminated by the current administration. We must demand that it be reinstated or risk the HIV epidemic rocketing out of control again. If that happens, we will have lost the good will we engendered, with follow-on effects of the Chinese Communist Party and Russia exerting influence, risking the collapse of economies, which will in turn destabilize countries and become a crisis of migration and political instability requiring a military response. To paraphrase General Mattis, cuts that weaken our soft power will require us to spend more on ammunition. I urge everyone who cares about public health and the US standing in the world to make their voices heard to their congress people about reinstating funds for global health, domestic infectious diseases, the NIH, CDC, and the FDA.

Manuel de la Cruz Gutiérrez, PhD, MLS, Director of the Holman Biotech Commons, shares his journey from studying physics in Guadalajara to leading one of Penn’s top research support centers. With a background in optics and biomedical research, he discovered his passion for supporting global health through library sciences. At Penn, he has played a key role in advancing research accessibility, collaborating with the Center for Global Health and initiatives like the Guatemala Health Initiative. He highlights the vital role of libraries in organizing health knowledge, supporting research, and providing essential resources to global researchers. Dr. de la Cruz Gutiérrez encourages students and faculty to explore the vast services of the Holman Biotech Commons, emphasizing that libraries are a critical partner in advancing healthcare, education, and discovery.

Manuel de la Cruz Gutiérrez, PhD, MLS, Director of the Holman Biotech Commons, shares his journey from studying physics in Guadalajara to leading one of Penn’s top research support centers. With a background in optics and biomedical research, he discovered his passion for supporting global health through library sciences. At Penn, he has played a key role in advancing research accessibility, collaborating with the Center for Global Health and initiatives like the Guatemala Health Initiative. He highlights the vital role of libraries in organizing health knowledge, supporting research, and providing essential resources to global researchers. Dr. de la Cruz Gutiérrez encourages students and faculty to explore the vast services of the Holman Biotech Commons, emphasizing that libraries are a critical partner in advancing healthcare, education, and discovery.

You’ve had a unique journey from studying physics in Guadalajara to your current role as Director of the Holman Biotech Commons. What led you to pursue this path, and how do you use your expertise to perform and support global research?

After my undergraduate studies, I became a graduate student at the University of Rochester in New York, in their PhD in optics program through a Fulbright scholarship. In the middle of it, I was a visiting graduate student at the University of Oxford so I was able to do 2 institutions in one degree! which was very nice and it exposed me to life in the UK. After being in Oxford for 3 1/2 years my wife and I came back to the United States and after finishing my PhD I became a postdoc at Baylor College of Medicine: that's when I switched from physics to biomedical research, doing neuroimaging of psychiatric disorders. I did that for about 3 years there at and at University of Houston, and it was during that time that I realized I was more myself –and feeling better suited– supporting research instead of performing it… and that's when I discovered that a librarian can do just that every day. I became a science librarian at the University of Houston –and did that for a about 3 years– and then I came to the University of Pennsylvania where I became a biomedical librarian with an interest in data services. After a promotion in 2019, I became director of Data and Innovation Services and, since last year (2024), I am the Director of the Holman Biotech Commons. Supporting research at the global scale is of interest to me because I have always been interested in different cultures, different languages, and I think at this point in time a global effort is necessary to address the existential problems we have as species.

What interests you most about the intersection of health and library sciences?

I think library science brings organizational principles and practices to healthcare information and health knowledge. It also supports health research, care delivery and training –it just makes health research and care more effective. Further, libraries provide authoritative information to healthcare organizations and practitioners so they can conduct their work with the best evidence, in a timely, accessible, a convenient manner.

How did you first get involved with the Center for Global Health? How does it complement the work you do in Library Sciences?

When I started working at Penn, the Guatemala Penn Partnership used to meet at what was then called the Biomedical Library –now the Holman Biotech Commons– and I started attending the meetings because of my interest in the Latin American region. In the meetings I started getting to know the Penn partners and their Guatemalan counterparts and seeing where the library could provide support. Actually, my library had already been involved with some initiatives in Guatemala by this point, and it was then natural for me to join in to those initiatives. I started working more closely with the CGH when I went in a trip with Penn professors to teach a workshop in implementation science in Guatemala City. I had the opportunity to teach attendants the ins and outs of researching the biomedical literature. In that trip, I also met a group of health sciences Guatemalan librarians interested in forming a consortium of Guatemalan libraries so they could better negotiate license deals for electronic journals. Supporting a center like CGH is an integral part of my job as a librarian at the University of Pennsylvania as it’s a key PSOM initiative, and the library is always trying to be supportive of the mission of the School.

What advice would you give students and global researchers at both Penn and our partner institutions on working with Penn and the Holman Biotech Commons?

Libraries are always here for you! come and see what services and resources we might have that could support your research, your clinical care, and your teaching –and for students, your learning. Every time that you are faced with a problem, I’d invite you to think “how could the library help me with this?” and come talk to us. Come through our doors, come through our websites, and see what we might have for you. We have a plethora of trustworthy, well curated information, and also excellent services and spaces that you can use on your daily workflows.

This February we spotlight Melissa Stockton, PhD, MSPH, a social epidemiologist and behavioral health researcher dedicated to improving mental health care in low-resource settings. With a career rooted in global public health, she specializes in implementing and evaluating behavioral health interventions, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. Her work in Malawi has focused on integrating depression treatment into HIV care, overcoming systemic challenges to expand access to mental health services. Passionate about community-driven, culturally relevant solutions, Dr. Stockton emphasizes strong partnerships and implementation science in her research.

This February we spotlight Melissa Stockton, PhD, MSPH, a social epidemiologist and behavioral health researcher dedicated to improving mental health care in low-resource settings. With a career rooted in global public health, she specializes in implementing and evaluating behavioral health interventions, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. Her work in Malawi has focused on integrating depression treatment into HIV care, overcoming systemic challenges to expand access to mental health services. Passionate about community-driven, culturally relevant solutions, Dr. Stockton emphasizes strong partnerships and implementation science in her research.

Background and Career Path

You are an epidemiologist working in behavioral health. What sparked your interest in this intersection of disciplines?

On a theoretical level, I’ve always been really interested in the social forces that shape health and well-being understand and the methods you can use “measure” or assign a numeric value to latent social-behavioral aspects of health. However, these days I like to say that I wear “many hats” in my work, at times a social epidemiologist, implementation scientists, or mixed methodologist. I think all these disciplines play a role in adapting, implementing and evaluating behavioral health interventions.

How has your career trajectory influenced your approach to global health research?

Unlike many, my career trajectory in global health has been largely linear. I studied international affairs and global health as an undergrad, my first “real job” was at RTI International in the Global Health Group, my graduate and doctoral work focused on HIV and mental health in sub-Saharan Africa, and I have worked entirely on research and programming outside of the US in low- and middle-income countries. In this way, a lot of my experience and thinking around global health is really rooted in public health in low-resource settings.

Research and Expertise

Your research focuses on mental health and behavioral interventions in low- and middle-income countries. Can you share a project that illustrates the challenges and impact of your work?

Yes! I like to joke that my doctoral research was just a thorough examination of how we “failed” to integrate depression screening and treatment into HIV care in Malawi. In this study, we trained existing staff at public health facilities to screen new ART patients for depression and offer either antidepressants or Friendship Bench problem solving therapy. However, time and resource constraints, lack of integration into the electronic medical record system, and varying attitudes towards the program ultimately resulted in very few depressed patients receiving depression treatment per-protocol. Unsurprisingly, the integrated program did appear to improve either HIV or mental health outcomes as expected.

However, the investment in capacity building and lessons learned from this study allowed for tremendous growth and expansion of depression care services in Malawi, and tailored implementation strategies to help overcome identified barriers. Today, depression care has been scaled-up in 12-districts across the country and tailored for both pregnant women and adolescents living with HIV.

If you’d like to read more about our original struggles, please see below:

Stockton, M.A., Minnick, C.E., Kulisewa, K., Mphonda, S., Hosseinipour, M. C., Gaynes, B. N., Maselko, J., Pettifor, A. E., Go, V., & B. W. Pence. (2021). A mixed-methods process evaluation: integrating depression treatment into HIV care in Malawi. Global Health: Science and Practice.

Stockton, M.A., Udedi, M., Kulisewa, K., M. C. Hosseinipour, Gaynes, B. N., Mphonda, S., Maselko, J., Pettifor, A. E., Verhey R., Chibanda, D., Lapidos-Salaiz, I., & B. W. Pence. (2020). The impact of an integrated depression and HIV treatment program on mental health and HIV care outcomes among people newly initiating antiretroviral therapy in Malawi. PloS One. 15(5), e0231872.

Behavioral health interventions are a key part of your expertise. How do you approach developing culturally relevant and effective interventions for diverse populations?

Strong partnerships and community-based participatory approaches are integral to ensuring interventions are culturally relevant and appropriate. As a continued plug for implementation science approaches to research – we already know a lot about which evidence-based practices can be implanted in diverse and low-recourse settings. I try to ensure that my research starts by drawing from the existing evidence-base. Then, we utilize robust community-based participatory models to ensure appropriate tailoring or fit within a specific context without losing fidelity to the underlying evidence-based principles.

Teaching and Mentorship

You work primarily in Malawi. How do your department and the Center for Global Health support you with mentoring students and early-career researchers interested in global health and behavioral health both at Penn and abroad?

The Psychiatry Department recognizes the increasing importance of global mental health, particularly as interrelated with global HIV prevention and control. To that end, I joined Penn as part of an effort to ensure that Penn is at the forefront of Global Mental Health research and programming. We are actively recruiting postdoctoral fellows as well as residents with a keen interest in Global Mental Health. The Center for Global Health has also been instrumental in connecting me with students and early-career researchers with an interest in gaining experience in global research or collaborating. Additionally, one of my close colleagues, Dr. James January from the Kamuzu University of Health Sciences in Blantyre, Malawi, will be attending Penn’s Implementation Science Institute Summer organized by the Center for Global Health.

Global Impact and Vision

Your international collaborations have spanned diverse settings. Could you describe a partnership that highlights the importance of cross-border teamwork in advancing public health?

You cannot implement health programs globally without strong, multisectoral collaborations. In Malawi, much of my work over the last 8 years has focused on implementing and evaluating evidence-based depression care services. I have had the honor of working with incredible partners within the Ministry of Health who have championed expanded access to evidence-based mental healthcare services. Without their support and direct engagement in tailoring the programs for this setting, training and supervising staff, and developing implementation strategies, none of this work would have been possible.

What emerging trends in global health and behavioral science excite you most, and how do you see them shaping your work in the coming years?

I have been excited to see a continued push for decolonizing global health research and strategically investing in research capacity, particularly in LMICs. Considering the country’s rapidly changing political environment, I hope that there will continue to be funding for this type of sustainable investment globally.

Broader Impact

In recent years, we have noticed an increased interest in global mental/behavioral health from clinical trainees. What kind of advice would you give to a student or trainee interested in a career in Global Mental Health Research?

Explore opportunities for experiential learning! There are many opportunities to get involved in global health research both at Penn Global Health Center (consider a Summer Research Experience or PSOM Year Out) and well as NIH-funded fellowships such as T32 training grants, Fulbright-Fogarty, etc. (assuming these will return). Also reach out to faculty who are engaged in research that interests you! Many are looking to engage interested students and trainees.

This January, we Spotlight Dr. Ryan Henrici an Adjunct Assistant Professor at Penn’s Perelman School of Medicine and Director of Translational Research at BigHat Biosciences. He combines personal inspiration and cutting-edge science to drive transformative advances in global health. Dr. Henrici pursued a PhD at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine before attending Penn Med. His research has spanned uncovering drug resistance in malaria to leveraging artificial intelligence for designing therapeutic antibodies, including critical breakthroughs during the COVID-19 pandemic. At Penn, he teaches courses in cell biology and infectious diseases, integrating his industry expertise to prepare students for the future of medicine while continuing to impact global health through innovation.

Early Influences and Education

What experiences and/or individuals inspired your interest in medicine and research, particularly in biochemistry and molecular biology?

When I was a child, my mother developed a progressive, paralyzing neurological disease that was challenging to diagnose. As a family, we spent years in and around hospitals ping-ponging between diagnoses and minimally effective treatments. In the early 2000s, a team at the Mayo Clinic identified autoantibodies that caused her disease and correctly diagnosed my mother with Neuromyelitis Optica. Her neurologist put together the research advances and clinical story to treat her with Rituximab, a monoclonal antibody, which permanently halted her disease. The team between Main Line Health and Penn Medicine provided exceptional care for my mother and our family and proved the power of compassion, purpose, and translational research. I wanted to offer this to other families in the future. During this time, my high school chemistry teachers Drs Wood and Best provided me an outlet from the stress at home by helping set up the chemistry labs and performing some very basic work on caffeine extraction from coffee beans. It was a fun, low-consequence, and formative experience from which I really caught the bug for science. At Penn State, I fell in love with molecular biology in Professor Song Tan’s crystallography and gene regulation lab. Over four years, I learned how a few creative people with perseverance, critical thinking, and a good idea can discover really exciting things.

You chose to complete a PhD prior to matriculating into medical school at Penn, which is unusual. Tell us how you chose that trajectory and how you reflect on that decision now.

While applying to medical schools as an undergraduate, I was awarded the Marshall Scholarship to complete my PhD in the UK, so I deferred my acceptance to the MD program at Penn to move to London. Although MSTP programs in the US were of interest, I was excited to study in the UK and at the LSHTM, which both have tremendous legacies in infectious diseases research and global leadership in tropical medicine and drug development for neglected diseases (the subject of my PhD). I knew my future career would greatly benefit from global training, and the Marshall Scholarship was the ideal opportunity. I strongly believe this training made me a better scientist and citizen, although completing my PhD before medical school probably made me a much worse medical student! Coming back to classes after years of increasing independence in the lab was a significant challenge.

How did your experiences as a Penn med student complement your approach to scientific inquiry and collaboration developed during your doctoral studies at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine?

Being a student at Penn gave me a human perspective on medicine and research that my lab-based doctoral training could not. I saw how patients and their families navigate the healthcare system in the context of their daily lives, and I saw how diseases can mimic each other, hide from our detection, and escape our best treatments. As a student I engaged with CGH to travel to Uganda after MS1 and spent the summer working on a Phase 3 study to reduce infections in children with Sickle Cell Anemia with Dr Chandy John (Indiana University) and Dr Ruth Namazzi (Makerere University). The combination of experiences as a medical student at Penn and doctoral student at LSHTM helped me see the signs of significant malarial drug resistance in these children. We collectively sought and receiving funding for a dedicated follow-up study involving Penn, LSHTM, IU, and Makerere that revealed the first evidence of drug resistance in patients with severe malaria.

Research and Career

Your work at BigHat Biosciences leverages artificial intelligence to develop therapeutic antibodies. Can you explain how this technology accelerates the development of treatments and why it’s transformative for infectious diseases?

Antibodies are some of the most powerful medicines we have in our arsenal today, controlling diseases as diverse as Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever, Neuromyelitis Optica (as for my mom), and many types of cancers. However, designing these antibodies is challenging. As scientists modify an antibody to improve one property, such as the ability to kill diseased cells, other properties, like stability or production rate, may suffer. This game of whack-a-mole is part of what makes drug development so slow and expensive. The relationships between these key properties are not obvious to humans, and the “search space” for good drugs is extremely large. Artificial intelligence and machine learning tools can learn these relationships, map the search space, and unlock rapid and more ambitious therapeutic research projects. For infectious diseases, this translates to antibodies that maintain their ability to neutralize pathogens even as those pathogens mutate and evolve. Additionally, we can engineer antibodies to persist in the body for many months so patients may receive doses once every six months and remain protected from infection – this is especially important for patients who may not develop robust immunity from vaccines for any number of reasons.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, your work centered on discovering therapeutic antibodies for SARS-CoV-2. What were some of the major challenges and breakthroughs from this research?

It was [challenging]! In the early months of the pandemic, very little was known about the SARS-CoV-2 virus, and few therapeutic antibodies were described. However, several antibodies against SARS-CoV, a related virus that caused a 2003 epidemic in Hong Kong, were previously published. One antibody had detectable but very weak binding to the SARS-CoV-2 virus, so we used machine learning tools to convert its specificity from SARS-CoV to SARS-CoV-2. Unlike most of the early monoclonal antibodies, this antibody maintained very broad neutralization of viral variants through the Omicron lineage about two years into the pandemic. In addition to building a remarkable antibody, this work paved the way for multiple new programs where we use AI/machine learning tools to tune the ability of antibodies to discriminate closely related proteins. Many high-value therapeutic targets belong to families of related proteins. Precise therapeutic targeting is essential to ensuring new drugs are effective and safe.

Teaching and Mentorship

It’s great to see that you stay engaged with teaching at Penn Med! Tell us about your role as an Adjunct Assistant Professor in the Department of Cell and Developmental Biology and how your industry role informs your teaching.

Teaching in MOD1 is a tremendous privilege. I teach a series of basic cell biology and physiology lectures in the Cell and Tissue Bio (CTB) and Embryology courses, and I give my favorite lectures in Vector-borne Diseases and Parasitology in the Microbiology/Infectious Diseases course. I got my start teaching in Micro/ID while still enrolled as a medical student, and the department faculty have graciously invited me to take on more lectures. My roles in industry and teaching really inform each other. I incorporate emerging topics in therapeutics and immunology like bispecific antibodies and antibody-drug conjugates into the classwork to make sure students understand what is coming through the pipe. By the time the students are in practice, today’s experiments will be tomorrow’s cures. Likewise, sharing in the students’ curiosities and commitment to a future in medicine provides purpose and keeps me grounded.

What do you enjoy most about teaching and engaging with Penn med students?

I love the enthusiasm that students bring to the lectures – even the 8am classes in Reunion! PSOM students are clearly motivated and really want to engage with and learn the course content. Their questions keep me on my feet and challenge me to deepen my own knowledge.

Broader Impact

What advice would you give to students or early-career researchers aiming to make an impact in translational medicine or infectious diseases?

Work on problems that really matter to you. Our world is full of grand and worthy challenges, and finding the problems that consistently keep you up at night can be daunting. My most stimulating opportunities were often the tangential ones that seemed like a detour. My entire PhD was in a field that I knew nothing about; my MS1 summer research took me to a new continent; and a work-study scheme in medical school led me to my current career leveraging machine learning to design medicines. Medicine can readily become a fast track of training and entry into practice. That track will always be there for you. Take the time to explore adjacent opportunities and understand your patients beyond their diagnoses. Who knows, you might just change your life.

Dr. John Holmes, a leader in medical informatics and epidemiology, shares insights on how informatics is transforming global health. From leveraging electronic health records and AI-driven solutions to improving healthcare in resource-limited settings, to fostering international collaborations in Botswana and Italy, his work bridges data science and public health. He discusses the critical role of interdisciplinary partnerships, data sharing, and mobile health innovations in shaping the future of global health. Passionate about education, Dr. Holmes also reflects on mentoring the next generation of informaticians and the evolving landscape of AI in medicine.

Dr. John Holmes, a leader in medical informatics and epidemiology, shares insights on how informatics is transforming global health. From leveraging electronic health records and AI-driven solutions to improving healthcare in resource-limited settings, to fostering international collaborations in Botswana and Italy, his work bridges data science and public health. He discusses the critical role of interdisciplinary partnerships, data sharing, and mobile health innovations in shaping the future of global health. Passionate about education, Dr. Holmes also reflects on mentoring the next generation of informaticians and the evolving landscape of AI in medicine.

Dr. Holmes, you've made significant strides in medical informatics within epidemiology, particularly with applications to global health. Can you share some examples of how your work in informatics has directly impacted global health initiatives?

There have been a few instances where my work at the intersection of informatics and epidemiology has had an impact on global health initiatives. Most recently, I’ve been deeply involved with the international Consortium for the Clinical Characterization of COVID-19 Using the Electronic Health Record (4CE). This initiative was started by my colleagues at Harvard Medical School in early March, 2020, and involved setting up a network that allowed us to share aggregated and deidentified health record data for millions of patients with COVID in seven countries in Europe, Latin America, and the US. Our first publication was deposited in MedRxiv, the medical preprint server, on March 30, owing to the speed with which this network was constructed. Since then, we have written over 15 peer-reviewed publications on disease severity; pediatric manifestations of COVID; neurologic, vascular, renal, and other complications; and most recently, “long COVID”. While most of these studies focused on clinical epidemiologic methods, they would not have been possible without the underlying information infrastructure and the application of novel machine learning methods that resulted from the collaboration of the informatics communities of more than 150 international participants in 4CE. These papers have been cited frequently, and I suspect that the information therein would have assisted policy makers, practitioners, and researchers in their work as they dealt with the pandemic. I have noted other contributions to global health initiatives below.

How do you envision advancements in medical informatics reshaping healthcare delivery in resource-limited settings globally?

I think there many domains in which informatics can help to reshape healthcare delivery in limited resource settings, but I immediately think of two. The first of these is in mHealth (“mobile health), which encompasses methods for bringing everyday experiences, such as physical activity, diet control, medication adherence, mood assessment, and many others into the hands of the public and ultimately to care providers. There are many applications that use devices such as smartphones, activity monitors, and continuous monitoring devices, to capture data as a person experiences their daily life. Such data extend far beyond what is captured during a patient encounter, and these methods have been shown to improve a variety of health outcomes. mHealth has the advantage of being supported on a wide infrastructure of wireless networks, as well. In my work in Botswana, we have used consumer-facing mHealth applications for tuberculosis contact tracing and extending medical education for students working in the field.

A second domain is the increasing availability of electronic health record (EHR) systems, especially those that are open-source and free of purchase-associated costs. Such a system as OpenMRS, a free EHR platform (https://openmrs.org) can be downloaded and installed on nearly any computer, even a modest laptop. Such systems do require some expertise in configuring the system to the needs of the provider or healthcare setting, but such expertise is globally available, as it is currently in use in Latin America, Africa, and South and Southeast Asia, and the Caribbean, with a large community of users who provide support to each other.

My colleague, Hamish Fraser, a physician-informatician now at Brown but formerly at Harvard, working with the late Paul Farmer and Partners in Health, was able to set up OpenMRS to manage the enormous health issues wrought from the 2010 earthquake in Haiti that destroyed most of the medical information infrastructure. Clearly, such EHR solutions are a cost-effective way to improve this infrastructure in many low-resource settings, but challenges do remain for many, including sometimes spotty availability of electrical power and ongoing maintenance of the system, which requires trained personnel on a long-term basis. However, the advantages of a robust yet cost-effective EHR system are myriad, such as those we enjoy here at Penn with our systems. This would include access to patient portals (such as we have in MyPennMedicine), patient monitoring, and ensuring continuity of care.

How do interdisciplinary collaborations, particularly in epidemiology and medical informatics, help address global health challenges? Are there partnerships or projects you’re currently involved in that are particularly promising?

The relationship between epidemiology and informatics has always been very tightly interwoven, but never so much as the present day. For example, data and the information we glean from them is critically important to making the kinds of inferences we make in epidemiology that can positively affect health, especially in low-resource settings. I have been honored to work over the past several years on the NIH-Fogarty International Center-funded training grant in injury epidemiology. This program, started under the leadership of Doug Wiebe, and which I took over after he left Penn for the University of Michigan, trained seven researchers in Botswana, leading to the Master of Science in Clinical Epidemiology (MSCE) degree. My most recent student, Keneilwe Motlhatlhedi, just graduated from Penn with her MSCE, with a thesis that characterized unintentional childhood injuries in rural Botswana. Her work, the first of its kind in Botswana, lays the much-needed foundation for additional work in this area that will lead to interventions that could reduce the incidence of such injury. Kene and I continue to collaborate, and I still look for ways that we can build on our collaborations with each of our former trainees.

I also have a long-standing relationship as a visiting professor at the University of Pavia (UPV) in Italy. There, my collaborations are primarily informatics-focused, but I am able to weave in my clinical and epidemiology background to enrich my collaborations with faculty there, but also with graduate students in biomedical informatics. Over the past 12 years, I have had the opportunity to work with and supervise several PhD students, two of whom are now on the faculty at Pavia. In addition, I have many other students with whom I have had the opportunity to provide more informal mentorship. Because of my relationship with UPV, several other students and post-doctoral trainees have come to Penn to work with other faculty in the Division of Informatics in the DBEI. I am looking forward to continuing this relationship with the goal of cross-fertilizing our two programs in biomedical informatics.

What role does data sharing and collaboration across borders play in advancing global health, and what challenges have you encountered in fostering such collaborations?

There is no question that data are the key to accomplishing the work of advancing health, and I think this is a widely shared opinion across the globe. The question is how to facilitate sharing data- and not just clinical, but also climate, environmental, insurance claims, and other data that we need to answer some very thorny research questions that could lead to improving health through effective surveillance and implementable and sustainable interventions. As an injury researcher as well as an informatician, I have seen first-hand how many gaps exist in other countries have created sometimes insurmountable challenges for researchers in both disciplines. For example, my most recent MSCE student, Kene, had enormous difficulty in just finding records of accident and emergency visits for injured children. At the worst, entire years of charts (which are paper-based, not electronic) were “missing”, and as a result, her planned observation period had to be truncated by two years. Fortunately, she was able to reach the desired sample size with the records she was able to retrieve, which were also the most recent visits. But even there, the records were rife with missing data- which is also a problem even in our electronic medical record systems- so overall data quality was compromised to some extent, and this is acknowledged in her work as a call to action. This is a place where informaticians need to take the lead, and there are some in Botswana who are doing just this.

A number of years ago, I worked with Drs. Carrie Kovarik (Penn Dermatology), Tony Luberti (CHOP), and Mr. Jonathan Crossette (CHOP) to help build health informatics capacity in Botswana. We had two large meetings (known as a pitso in Setswana) that involved clinicians, computer scientists, researchers, and officials from the Botswana Ministry of Health. During those meetings, we exposed the importance of “good data” for improving patient care and for clinical and epidemiologic research. We also had the opportunity to work with a truly stellar individual, Kagiso Ndlovu, who at the time was associated with the computer science department at the University of Botswana (UB). All of us developed a close collaboration with him, and over time, went on to a PhD at the University of KwaZulu-Natal. With assistance from colleagues at CHOP and myself, Kagiso set up the instance of REDCap at UB, which made available this remarkable data collection and management resource to scores of researchers in Botswana.

Congratulations on the Christian R. & Mary F. Lindback Award for Distinguished Teaching! How does your teaching approach in medical informatics prepare students to address real-world global health challenges?

Thank you so much! It really has been humbling to be honored with the Lindback, and I hope I am worthy of this award as I continue to teach. My history of teaching trainees from all over the globe extends back to when I first rejoined Penn Medicine in 1982 as a junior research coordinator in what was then the Clinical Epidemiology Unit (CEU) in the Section of General Internal Medicine. Because I had substantial experience in computing, having worked in what was then the Pulmonary Disease Section at HUP (we developed methods for computerizing pulmonary function tests, and I had the opportunity of lecturing medical students on how these methods worked), I was appointed the “computer guy” for the CEU. Not only was I responsible for setting up a lab with two Apple-II+ computers but also training fellows in the International Clinical Epidemiology Network (INCLEN) program, for which we were one of three regional research training centers. I developed courses in basic computing (new at the time!), database theory, and data management for clinical research. Through this program I taught dozens of wonderful INCLEN fellows- mostly physicians and mostly faculty- from Latin America, India, Africa, and Southeast Asia, and had the opportunity to hone my skills in teaching international students. I owe the world to them, as they taught me how to adjust my teaching methods to accommodate students coming from diverse, low-resource environments. Through my many conversations with them outside of the classroom about their needs as students and what I should be doing to address those needs (avoiding slang and jargon was a good start, but not the only thing), I learned more from them than they from me. I continue to build on my experience with INCLEN to inform how I teach informatics (and epidemiology) today- whether the students are international or domestic.

How do you balance teaching with the demands of your global research, and how do your students contribute to or influence your research in global health?

This is a good question, and one that I know junior faculty wrestle with as they approach promotion. In addition to what I have noted above with regard to my former INCLEN students, I try to incorporate my research interests and program with what I teach. This is not to say that I focus on presenting my own work in the classroom; in fact, I avoid citing myself at every turn, unless it is absolutely germane to a particular topic. Rather, I have found over the years that much of my research has developed through teaching, constantly encountering students who have unique and interesting ideas on which I have been invited to collaborate. A good example of this is my work with Arianna Dagliati, a former PhD student from the University of Pavia who was doing her post-doctoral training at the University of Manchester (UK), where I also have had a number of collaborations. Her project focused on developing topological models of chronic disease progression. I had not worked in topology before, but as one with an interest in network models and advanced mathematics, I was immediately intrigued. Since then, we have developed a long collaboration in this area that has continued through the COVID-19 pandemic, where we continue to use these models to discover the “surface” of contagion in various environmental settings. So, if one is open to learning from their students about such opportunities, there is no reason to believe that one’s research program has to suffer because of teaching commitments; rather, they go hand-in-hand as part of the big picture of what I feel it means to be an academic.

Looking forward, what emerging trends in medical informatics do you believe will most significantly impact global health, and are there specific projects you are excited to pursue?

I think pretty much everyone is aware of the way that artificial intelligence (AI) has captivated just about every quarter of society, and this true globally. Certainly, AI holds much promise for improving certain aspects of healthcare, disease surveillance, and epidemic response. I do fear that much of this promise is compromised by so much hype and a lack of circumspection about what AI actually is. That said, AI in health is a huge area of research and implementation in biomedical informatics, and that is a good thing. If we can focus on the small wins that AI can afford us in global settings, especially low-resource ones, we will be much better off and less likely to experience dashed expectations and rejection of the technology, which has happened twice before in the history of AI- first with expert systems and second with early neural networks. Applying AI tools to domains in which it can make incremental, yet meaningful, differences in health and healthcare is really the most important thing we can do now. For example, the mHealth tools I described above could be improved with better context-sensitive data collection from, and feedback to, patients. Or, AI could be used to improve clinical workflows in low-resource settings with overcrowded clinics. These are the types of domains where early, and relatively easy, wins would really show and fulfill the promise of AI. We in better-resourced settings are already doing this, but we need to think more about how to accomplish this in less-advantaged settings throughout the world.

What advice would you offer to students and young professionals interested in combining medical informatics with global health, especially as the field continues to evolve?