Research Projects

I. Understanding Allostery in Inborn Errors of Metabolism

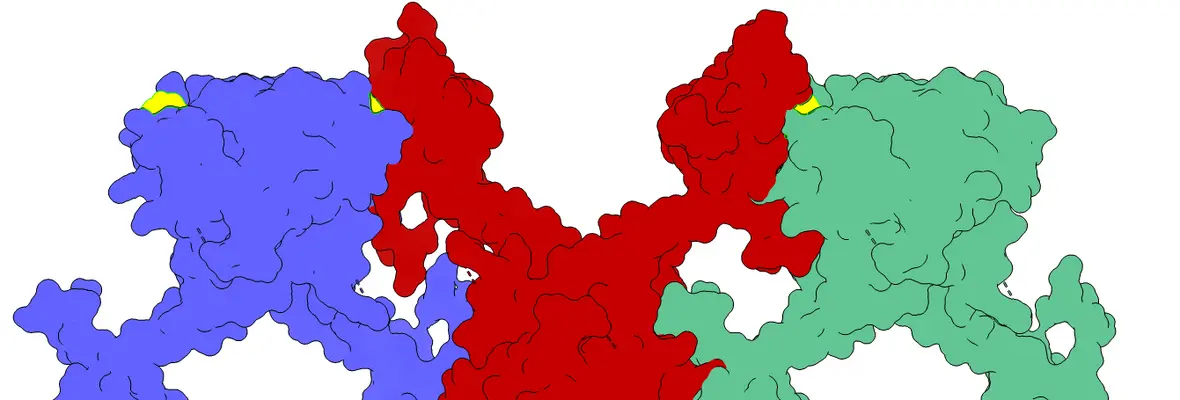

We aim to understand the structure and mechanism of enzymes underlying inborn errors of metabolism (IEMs). Our initial studies focused on phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH), the enzyme deficient in phenylketonuria (PKU). In collaboration with the Jaffe lab at Fox Chase Cancer Center, we solved the first intact structures of rat and human PAH in its resting form and developed a novel model for its allosteric transition. This work has expanded to include other allosterically regulated oligomeric enzymes involved in IEMs, such as cystathionine β-synthase (in collaboration with Warren Kruger at Fox Chase Cancer Center), pantothenate kinase (in collaboration with Zolt Arany at Penn), and porphobilinogen synthase.

Selected Publications:

- Lee HO, Wang L, Gupta K, et al. Impact of primary sequence changes on self-association properties of mammalian cystathionine β-synthase enzymes. Protein Sci Dec;33(12):e5223 (2024).

- Arturo EC, Merkel GW, Hansen MR, et al. Manipulation of a cation-π sandwich reveals conformational flexibility in phenylalanine hydroxylase. Biochimie 183:63–77 (2021).

- Arturo EC, Gupta K, Hansen MR, et al. Biophysical characterization of full-length human phenylalanine hydroxylase. J Biol Chem 294(26):10131–45 (2019).

- Arturo EC, Gupta K, Héroux A, et al. First structure of full-length mammalian phenylalanine hydroxylase reveals the architecture of an autoinhibited tetramer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113(9):2394–99 (2016).

II. The Structural Biology of Retroviral Integrases

Retroviral integrases (IN) catalyze the integration of viral cDNA into the host genome. In HIV, IN is a validated therapeutic target, with five FDA-approved drugs currently in clinical use. Since 2010, my research has focused on the structural biology of retroviral IN, including its higher-order organization, interactions with host factors, and, more recently, interactions with novel antivirals currently in clinical trials. Key contributions include experimentally confirming the quaternary structure of the intasome—a critical assembly in viral integration—using small-angle X-ray and neutron scattering (SAXS/SANS). Recent work centers on a new class of potent HIV antivirals known as allosteric inhibitors of integrase (ALLINIs), now in human trials. These drugs target the IN–LEDGF/p75 interaction but unexpectedly block viral particle formation rather than directly inhibiting DNA integration. In 2016, we achieved a breakthrough by solving the first crystal structure of full-length HIV-1 IN bound to the ALLINI GSK1264, revealing a novel mechanism of drug-induced branched polymerization of IN. Subsequent studies have explored viral escape mutations, the role of oligomerization, and strategies to optimize this promising class of small molecules.

Selected Publications:

- Montermoso S, Eilers G, Allen A, Sharp R, Hwang Y, Bushman FD, Gupta K*, Van Duyne GD*. Structural consequences of ex vivo ALLINI resistance mutations on the formation of drug-induced branched polymers of HIV-1 integrase. J Mol Biol Sep 1;437(17):169224 (2025). *Co-corresponding authors

- Eilers G*, Gupta K*, Allen A, et al. Structure of a minimal HIV-1 IN-allosteric inhibitor complex at 2.93 Å resolution: Routes to inhibitor optimization. PLoS Pathog. Mar;19(3):e1011097 (2023).

- Gupta K, Allen A, Giraldo C, et al. Allosteric HIV integrase inhibitors promote formation of inactive branched polymers via homomeric carboxy-terminal domain interactions. Structure 29(3):213–225.e5 (2021).

- Eilers G, Gupta K, Allen A, et al. Influence of the amino-terminal sequence on the structure and function of HIV integrase. Retrovirology 17(1):28 (2020).

- Gupta K*, Turkki V*, Sherrill-Mix S, et al. Structural basis for inhibitor-induced aggregation of HIV integrase. PLoS Biol 14(12):e1002584 (2016).

- Gupta K, Brady T, Dyer BM, et al. Allosteric inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus integrase: late block during viral replication and abnormal multimerization involving specific protein domains. J Biol Chem 289(30):20477–88 (2014).

- Larue R, Gupta K, Wuench C, et al. HIV-1 integrase C-terminal domain interacts with the cargo domain of TNPO3 in vitro. J Biol Chem 287(41):34044–58 (2012).

- Gupta K, Curtis J, Krueger S, et al. Solution conformations of prototype foamy virus integrase and its stable synaptic complex with U5 viral DNA. Structure 20(11):1918–28 (2012).

- Gupta K, Diamond T, Hwang Y, et al. Structural properties of HIV integrase–LEDGF oligomers. J Biol Chem 285(26):20303–15 (2010).

III. Nanoparticle Carriers for Therapeutics

Our group is pioneering biophysical approaches to analyze mRNA- and DNA-containing lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) using solution biophysics. Techniques include analytical ultracentrifugation, multi-angle light scattering (MALS), and small-angle scattering (SAXS). In collaboration with the Alameh, Brenner, and Mitchell labs at Penn, we are advancing the understanding of structure–function relationships in LNP formulations. By employing tools like multi-wavelength AUC (MW-AUC) and size-exclusion chromatography coupled with SAXS (SEC-SAXS), we have established key links between LNP composition, assembly, and their biological effects in T cells and mouse models.

Selected Publications:

- Padilla MS, Shepherd SJ, Hanna A, et al. Insights into mRNA lipid nanoparticle polydispersity and shape using quantitative solution biophysics. bioRxiv (In revision, 2025). *Co-corresponding authors

- Nong J*, Gong N*, Tiwari S, et al. Multi-stage mixing to create a core-then-shell structure improves DNA-loaded lipid nanoparticles’ transfection by orders of magnitude. bioRxiv (In revision, 2025).

- O’Brien ES, Fuglestad B, Lessen HJ, et al. Membrane proteins have distinct fast internal motion and residual conformational entropy. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 59(27):11108–14 (2020).

- Fuglestad B, Gupta K, Wand AJ, Sharp KA. Water loading driven size, shape, and composition of CTAB/hexanol/pentane reverse micelles. J Colloid Interface Sci 540:207–17 (2019).

- Fuglestad B, Gupta K, Wand AJ, Sharp KA. Experimentally benchmarked molecular dynamics simulations of CTAB/hexanol reverse micelles. Langmuir 32(7):1674–84 (2016).

IV. Spinal Muscular Atrophy

The SMN protein forms the oligomeric core of the SMN complex involved in snRNP biogenesis. Mutations in the SMN1 gene cause spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), a severe neurodegenerative disorder. My work focused on the oligomeric properties and structure of SMN–Gemin2. Using SAXS and analytical ultracentrifugation, we discovered significant conformational changes in Gemin2 upon SMN binding and revealed a dimer–tetramer–octamer equilibrium in the SMN YG box domain.

Selected Publications:

- Gupta K, Wen Y, Ninan NS, et al. Assembly of higher-order SMN oligomers is essential for metazoan viability. Nucleic Acids Res Jul 21;49(13):7644-7664 (2021).

- Gray KM, Kaifer KA, Baillat D, et al. Self-oligomerization regulates stability of SMN isoforms by sequestering an SCF^Slmb degron. Mol Biol Cell 29(2):96–110 (2018).

- Gupta K, Martin R, Sharp R, et al. Oligomeric properties of SMN·Gemin2 complexes. J Biol Chem 290(33):20185–99 (2015).

- Martin R, Gupta K, Ninan NS, et al. The survival motor neuron protein forms soluble glycine zipper oligomers. Structure 20(11):1929–39 (2012).

- Sarachan KL, Valentine KG, Gupta K, et al. Solution structure of the core SMN–Gemin2 complex. Biochem J 445(3):361–70 (2012).

V. Site-Specific Recombination

Site specific recombinases facilitate viral genome integration, multimer resolution, and transgene expression. Using crystallography, SAXS, and biochemical assays with the Van Duyne group, we have examined mechanisms of recombination directionality and synapsis.

Selected Publications:

- Li H, Sharp R, Rutherford K, et al. Serine integrase attP binding and specificity. J Mol Biol 430(21):4401–18 (2018).

- Gupta K, Sharp R, Yuan JB, et al. Coiled-coil interactions mediate serine integrase directionality. Nucleic Acids Res 45(12):7339–53 (2017).

- Mandali S, Gupta K, Dawson AR, et al. Control of recombination directionality by the Listeria phage A118 protein Gp44. J Bacteriol 199(11) (2017).

- Gibb B, Gupta K, Ghosh K, et al. Requirements for catalysis in the Cre recombinase active site. Nucleic Acids Res 38(17):5817–32 (2010).

- Yuan P, Gupta K, Van Duyne GD. Tetrameric structure of a serine integrase catalytic domain. Structure 16(8):1275–86 (2008).

- Ghosh K, Lau C, Gupta K, et al. Preferential synapsis of loxP sites drives ordered strand exchange in Cre-loxP site-specific recombination. Nat Chem Biol 1(5):275–82 (2005).

VI. Prostaglandin H₂ Synthase-1

As a graduate student, I studied the structure and mechanism of prostaglandin H₂ synthase-1, the NSAID target enzyme. My work led to multiple X-ray structures of the enzyme bound to inhibitors and alternative cofactors, revealing key aspects of NSAID action and enzyme evolution.

Selected Publications:

- Gupta K, Selinsky BS. Bacterial and algal orthologs of prostaglandin H₂ synthase: novel insights into evolution. Biochim Biophys Acta 1848(1 Pt A):83–94 (2015).

- Gupta K, Selinsky BS, Loll PJ. 2.0 Å structure of prostaglandin H₂ synthase-1 with a manganese porphyrin cofactor. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 62(Pt 2):151–6 (2006).

- Gupta K, Kaub CJ, Carey KN, et al. Manipulation of kinetic profiles in 2-aryl propionic acid COX inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 14(3):667–71 (2004).

- Gupta K, Selinsky BS, Kaub CJ, et al. 2.0 Å resolution crystal structure of PGH₂ synthase-1. J Mol Biol 335(2):503–18 (2004).

- Selinsky BS*, Gupta K*, et al. Structural analysis of NSAID binding: time-dependent and -independent inhibitors elicit identical enzyme conformations. Biochemistry 40(17):5172–80 (2001). *Co-first authors