- Our History

- The History of Neurology and Timeline

- Timeline

- Pre 1871 --- What was happening: Benjamin Rush, Civil War

Pre 1871 --- What was happening: Benjamin Rush, Civil War

Before there was a Department of Neurology…. Before there were Neurologists: Pre-Civil War Philadelphia’s medical and intellectual climate

The intellectual foundations of what became the Department of Neurology at the University of Pennsylvania go back nearly one hundred years before Horatio Wood formalized the division. To trace the climate changes of the time, we need to go back to Benjamin Rush, an extraordinary polymath, the only physician signer of the Declaration of Independence, Washington’s surgeon general, advocate for ratification of the Constitution, and founder of Dickinson College. Above all, he is an example both of the intellectual constraints of his time and of prescient understanding of the interplay between social conditions and medical problems and of the physical underpinning of mental disorders.

First, some flavor of the times, both medical and political:

The 19th century was a time of great intellectual revolutions on both sides of the Atlantic:

Those interested in empiric science began to call themselves “Scientists” as opposed to “Natural Philosophers”.

Phrenology enjoyed brief popularity leading to localization theory- (there were some missteps such as construing color blindness as “infarction in a hypothetical center for colors”). In 1828, a description of aphasia appeared in the Am J Medical Sciences” quoting the patient as saying, “didoes doe the doe “The phenomenon was described as “amnesia for words.”

Recognition of inflammation of the brain in asylum inmates with “general paralysis of the insane” (syphilis or la maladie de Bayle) established the possibility that some mental illness could have a physical cause recognition of general paresis of insane (Bayle 1822-26) and Burrows, owner of a private asylum in England.

Physicians calling themselves neurologists sought to differentiate themselves from psychiatrists who ran asylums. They wanted to do autopsies and find the lesions. German/Swiss/ French neurology was considerably ahead of American development, but American physicians were going through similar birth pains to separate from psychiatry and devote themselves to study of the anatomy (Harrington) of psychiatric illnesses. Unclear when the first known use of the word “neurologist” appeared—possibly 1832—but likely much earlier.

Asylums were the source of description of neurologic disease such as those in Reports of the West Riding Asylum (later to be the journal we know as Brain) –one building of the West Riding Asylum, minus its wings, was left as today’s Imperial War Museum in London). American asylum architects produced buildings similar to British architecture.

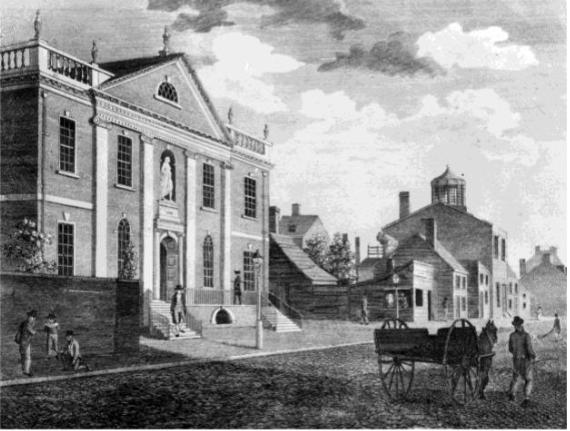

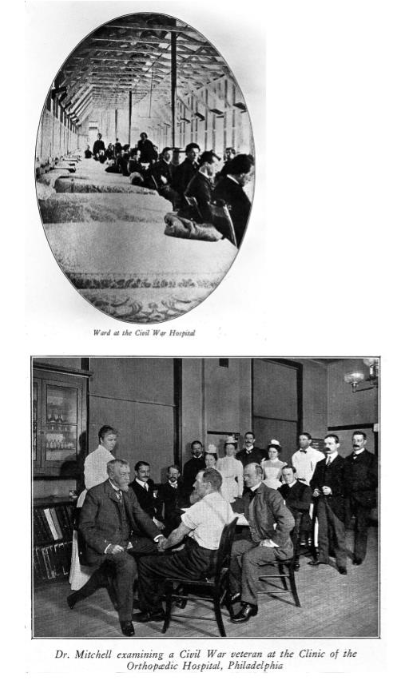

Hospital (pictured above) suffered from patient abuses and an important

role of the nascent specialty of neurology was to advocate for more humane

care of such problems.

The asylum story figured directly into the development of neurologic practice in the US. See below section on other developments in early American neurology for a discussion of the outcome of the dispute between psychiatrists and neurologists as to who should care for asylum patients.

Meanwhile, back in the very new USA:

Contemporaries Benjamin Rush (BR) and Alexander Hamilton (AH) shared many bonds (many of which frayed). Hamilton bought Rush’s house when BR moved to Third and Walnut. Philip Hamilton (later, like his father, to die in a duel) and Rush’s second son Richard were good friends.

Politics and Medicine: Rush disagreed with Hamilton on almost everything political. Though BR had started out as a Federalist and was friendly with John and Abigail Adams, he came to side with Jefferson. (though toward the end of his life BR was responsible for the reconciliation and resumption of correspondence of Adams and Jefferson.)

Hamilton probably blocked Rush’s appointment to AH’s alma mater Columbia as chair of medicine. Rush took a job at the US mint (easier to change careers then…)

With an unfortunate parallel to today’s politicization of medical issues, the yellow fever epidemic of 1793 struck with terrible swiftness (see Appendix 1 for CIVIL WAR medical terms for this and other conditions). One of the early theories attributed the fever to damaged coffee on one of the wharves north of Market Street.

Recommendations from Rush and others included:

- no church bell tolling at funerals- too many were dying

- aromatherapy—garlic vinegar, camphor chewing tobacco

- burning gunpowder

- purges: mercury, bloodletting

Medical advice about yellow fever was politicized just as COVID vaccines are today:

Hamilton took “the Federalist cure” which meant no purging and bloodletting as opposed to Rush’s advice. Rush fumed “If the new remedies had been introduced by another person than a decided Democrat and friend of Madison and Jefferson, they would have met with less opposition from Colonel Hamilton.” Rush believed that the Black population of Philadelphia was immune to yellow fever, though he later changed his mind. The Black community played a huge role in nursing of the sick and burial of the dead as white citizens fled —BR described the alternative treatments as the “French remedies” and this was not a compliment.

Benjamin Rush and Race: Rush was active in the Abolition Society and in fund-raising for Philadelphia’s first black church: the AE Church of St. Thomas. On yet the other hand, though, Rush announced in a 1797 paper his theory about black skin being an inherited remnant of leprosy. Jefferson and others disagreed and accused BR of being “in haste to teach what he had not learned.’” This was perhaps the most spectacular wrong-headed address of his career as both a doctor and an abolitionist.

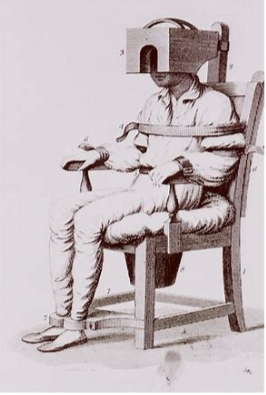

Rush and Mental Illness: In other areas of his far-reaching intellectual interests, BR was ahead of his time doing seminal work with mental illness. He was described by contemporary French traveler Jacques-Pierre Brisot as “the enlightened and humane Dr. Rush”. He argued to transfer mentally disturbed patients from a basement space to a furnished cell with views of gardens (patients in the basement cells were dying of TB) He conceived of a swing chair to “regulate blood flow to brain”. Surely a major impetus for BR’s interest in mental illness came from close to home in the form of his son John’s behavioral troubles.

Founding Fathers share Fatherly Familial Woes: BR, AH and John Adams share a sad commonality in the fates of some of their children. Rush’s son John killed a friend in a duel while a naval officer. Troubled with what today we might recognize as bipolar symptoms, he lasted for 4 months in college at Princeton (expelled for playing cards…), and returned to Penn, but later attempted suicide. Correspondence among Adams and Rush (Adams seeking Rush’s medical advice) bemoan the fact that John Rush and Charles Adams suffered from alcoholism, then just beginning to be recognized as a physical disease and an example of contemporary biomedical struggles with notions of heredity and transmission of disease. (Alcohol had long been a principal drug in the pharmacopoeia and the “brandy treatment” was recommended for disease as dissimilar as congestive heart failure and typhus). Charles Adams died from alcoholism.

Rush advocated for many improvements in mental health care. One of his ideas, the Tranquilizer Chair (below), did not enjoy a long life, but other suggestions did. In 1794 Pennsylvania Hospital agreed to build a new West Wing for mental health. As an interesting aside- some years after Rush’s death Edwin Forest, who was playing Othello in NYC and was about to take on King Lear, came to Pennsylvania hospital to see madness in the form of the then hospitalized John Rush (so much for HIPAA)– Edwin Forrest went on to become first internationally acclaimed Shakespearean actor born in the US.

In 1812, Rush published Medical Inquiries and Observations upon the Diseases of the Mind – He stressed that “Diseases of the mind and body are moved by the same cause and Subject to the same laws.” Somewhat daringly, he questioned whether the visions of the Apostles and others might have been on an organic basis and wondered if mentally ill persons could be held personally and criminally responsible for their crimes.

Rush and the Penn Connection

The University of Pennsylvania was created when College of Philadelphia merged with the University of the State of Pennsylvania. Rush became professor of the institutes of medicine and of clinical medicine. Classes were held at Surgeons Hall at 5th and Walnut (below). He also wrote an annual Introductory Lecture to courses of lectures about the “Institutes and Practise of Medicine”. This orientation event sounds somewhat like the white coat ceremony today.

The trajectory of a remarkable life: The father of 9 children, Benjamin Rush died in 1813 at 68. He is buried at the Christ Church Burial Ground near Constitution Center.

Ever the physician, Rush saw the experiment in America as a series of diagnoses; if something was wrong, he could fix it. He thought of health in the broadest definition of the word according to Rush biographer Stephen Fried physical health, mental health, spiritual health, economic health, political health public and private health. “

Importantly, he had the modesty and self-awareness to know that things he believed would be proved wrong but that some of his theories would be proved correct long after his own time that was not ready to accept them:

“The most acceptable men in practical society have been those who have never shocked their contemporaries by opposing popular or common opinions. Men of opposite characters, like objects placed too near the eye are seldom seen distinctly by the age in which they live. They must content themselves with the prospect of being useful to the distant and more enlightened generations which are to follow them.”

Aftermath: an assessment of Benjamin Rush’s legacy:

Rush Medical College in Chicago, chartered in 1837, just before the city itself was chartered.

S. Weir Mitchell at the 100-year anniversary of the College of Physicians in 1887 spoke highly of him and pointedly ignored BR’s possibly want of support of Washington at the darkest hours of the Revolution.

At this anniversary – AMA was now thirty years old and had just started publishing its journal.

AMA decided that Rush should be honored with a statue in Washington DC.

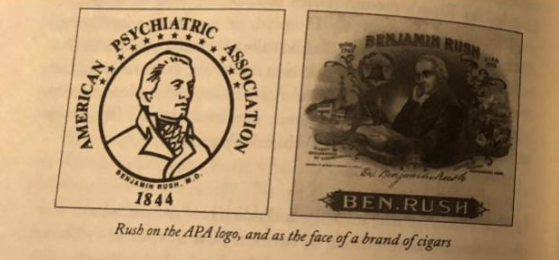

1844: Association of Medical Superintendents of American institutions for the insane founded by Rush’s heir Dr. Thomas Kirkbride at the Institute of Pennsylvania Hospital –at its 50th anniversary in the 1890s it was renamed the American Medico Psychological Association, and it adopted as its log a sketch of rush with 13 stars over his head (manufacturers of a cigar brand also chose to “honor” him). This later became the American Psychiatric Association

More than place names or statues (or cigar boxes) , Rush’s prescient insightful legacies include:

- disease killed more soldiers than bullets.

- mental illness and addiction were diseases that deserved to be treated as medical conditions.

- advocacy for public schooling, opening education to women African Americans, and non-English speaking immigrants.

- mental illness should be considered a mitigating factor in punishment of crime.

Other Developmental Themes in Early American Neurology

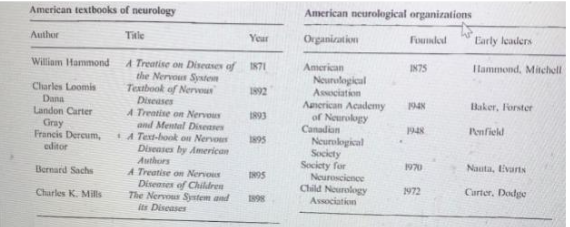

American published textbooks began to appear: 1871 William Hammond published Treatment of diseases of the nervous system ( in which he specifies left mca pathology leading to aphasia, noted that aphasia does not usually occur with right mca pathology, described embolism from endocarditis and coined the term athetosis) – this text was used for at least a generation (Both Hammond and Mitchell also wrote popular novels!) Then, as often now, a neurologic career was an autosomal dominant trait: Both Hammond and Mitchell had sons who carried on their tradition and took over their practices.

American Hospitals for Neurologic Problems: Turner’s Lane Hospital 1863, only 4 years after Britain’s establishment of the “National Hospital for the relief of paralysis, epilepsy and allied disorders” (now Queen Square). S Weir Mitchell described Horner’s syndrome before Horner, phantom limb pain, and Causalgia (now RSD or CRPS), 1864. His contributions to Civil War solider and veteran care are described in a different segment of this history project.

Neurology or Psychiatry? Then, as now, there was disagreement about somatic symptoms and this controversy figured into the founding of the American Neurological Association (ANA) . After losing the battle to take over care of asylum patients in 1870s (self-styled neurologists accused the asylum directors of being more interested in architecture than medicine), American neurologically oriented doctors couldn’t really find academic positions or fill their practice with clearcut neurological disease—so “nerve doctoring” took on a different meaning . Exhaustion, tremors, joint pain, insomnia, waves,of heat and cold, tics, sensory disturbances , headaches were symptoms that filled the offices of neurologists. By the 1870s in US patients who visited “nerve doctors” were more likely to be diagnosed not with “hysteria” but with neurasthenia. Invented by George Beard, the term connoted a state of “nervous exhaustion”, a breakdown in the overall function of a person’s “nerves.” - These patients did not want to go to a “lunatic asylum” instead they got massage, rest, exercise, or electrical stimulation.

In 1876 at the new ANA George Beard said that mental factors especially “expectation “seemed to be involved in his private practice cases. He just told them he would get better on a certain day or hour. Many patients exhibited relief. – He wanted to integrate a “talking cure; into their therapies—William Hammond was outraged – “we should join the theologians”—he refused to endorse ANA if they took on these ideas.” (After all that’s how Freud started out). In fact, many of the prominent members of the American Psychanalytic Association originally trained as neurologists.

Two developments are of particular note and underscore the flavor of unexplained symptoms and the contemporary technologic and spiritual trends:

- Train travel added to patients – “railway spine” or “railway brain”: back pain, trembling, numb limbs headache anxiety, insomnia and memory deficits.

- Christian Science – along with a number of other mind cure movements

A slightly random collection of other notable firsts:

Phantom Limb pain first reported in that great medical journal, The Atlantic Monthly

Causalgia—attempted morphine treatment by injection directly into wound – first use of hypodermic needled (didn’t work)

Medicolegal Advocacy:

There is a long British precedent for insanity defense based on notion of organic disease: including for the defendant Hadfield in 1800. Hadfield had made one of 6 attempts on the life of George III- the defense was rejected and Hadfield was hanged.

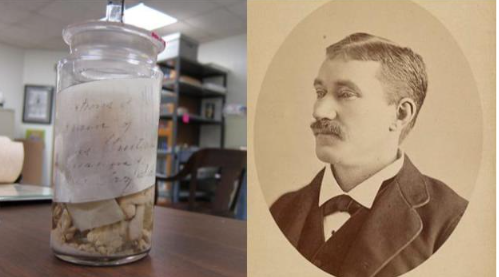

William Hammond testified for the defense in several insanity cases.

At the trial in 1882 of President Garfield’s assassin, Charles Guiteau was defended by American neurologist Edward Charles Spitzka who insisted that he was not responsible for what he did because he had a “congenital malformation of the brain” (This was based on fairly shaky evidence—tongue deviated to left. Guiteau was hanged but idea that organic pathology could cause criminal behavior remained attractive: the Mutter Museum acquired part of his brain and is still on display. Guiteau had an enlarged liver, possibly from malaria and probably had small vessel ischemic disease—the question of neurosyphilis was raised.

Conclusions:

This section has been a broad overview of intellectual, political, and medical developments in the early years of the Republic and of the field of neurology. There were missteps, but we should not smile condescendingly at our predecessors’ misconceptions. In fact, there are sometimes rather striking parallels with the controversies of our time. We would do well to remember the words of a renowned 19th century physiologist, Sir Michael Foster (1836-1907):

“For indeed it is one of the lessons of the history of science that each age steps on the shoulders of the ages which have gone before. The value of each age is not its own, but is in part, in large part, a debt to its forerunners. And this age of ours if, like its predecessors it can boast of something of which it is proud, would, could it read the future, doubtless find also much of which it would be ashamed.”

– from his Lectures on the History of Physiology

References and Sources:

Anne Harrington. The Mind Fixers: Psychiatry’s troubled search for the biology of mental illness. Norton: London, 2019.

Stephen Fried. Rush: Revolution, madness and the visionary doctor who became a founding father. Random House: New York, 2018.

FR. Fremon American Neurology in: Handbook of Clinical Neurology Chapter 38, pp 605-612, 2010.

Richard Hunter and Ida Macalpine. Three Hundred Years of Psychiatry 1535-1860. Oxford University Press: London 1963.

APPENDIX 1 : Civil War Terms

(from OSU Library) Which ones would you recognize today-which have disappeared, reflecting changes in understanding of disease causation?

(Diseases found on Death Certificates)

- Ablepsy - Blindness

- Ague - Malarial Fever

- American plague - Yellow fever.

- Anasarca - Generalized massive edema..

- Apoplexy - Paralysis due to stroke.

- Atrophy - Wasting away or diminishing in size.

- Bad Blood - Syphilis

- Bone shave - Sciatica

- Brain fever - Meningitis

- Breakbone - Dengue fever

- Casopisy - Irregular pulse.

- Caduceus - Subject to falling sickness or epilepsy.

- Catalepsy - Seizures / trances.

- Catarrhal - Nose and throat discharge from cold or allergy.

- Cerebritis - Inflammation of cerebrum or lead poisoning

- Chorea - Disease characterized by convulsions, contortions and dancing.

- Consumption - Tuberculosis.

- Corruption - Infection

- Delirium tremens - Hallucinations due to alcoholism

- Dock Fever - Yellow fever

- Dropsy of the Brain - Encephalitis

- Eclampsia - Symptoms of epilepsy, convulsions during labor

- Ecstasy - A form of catalepsy characterized by loss of reason.

- Falling sickness - Epilepsy

- Fits - Sudden attack or seizure of muscle activity.

- Flux - An excessive flow or discharge of fluid like hemorrhage or diarrhea..

- French Pox - Syphilis

- Glandular Fever - Mononucleosis

- Great Pox - Syphilis

- Heat Stroke - Body temperature elevates because of surrounding environment temperature and body does not perspire to reduce temperature. Coma and death result if not reversed

- Hectical Complaint - Recurrent fever

- Hemiplegia - Paralysis of one side of body

- Horrors - Delirium tremens

- Hydrocephalus - Enlarged head, water on the brain- with/without enlarged head

- Hydrophobia - Rabies

- Infantile Paralysis - Polio

- Lockjaw - Tetanus or infectious disease affecting the muscles of the neck and jaw. Untreated, it is fatal in 8 days.

- Long Sickness - Tuberculosis.

- Lues Disease - Syphilis.

- Lumbago - Back pain.

- Marasmus - Progressive wasting away of body, like malnutrition.

- Meningitis - Inflations of brain or spinal cord

- Morphew - Scurvy blisters on the body

- Myelitis - Inflammation of the spine

- Myocarditis - Inflammation of heart muscles

- Nervous Prostration - Extreme exhaustion from inability to control physical and mental activities

- Neuralgia - Described as discomfort, such as "Headache" was neuralgia in head

- Palsy - Paralysis or uncontrolled movement of controlled muscles. It was listed as "Cause of death"

- Paroxysm - Convulsion

- Phthisis Chronic - wasting away or a name for tuberculosis

- Pott's Disease - Tuberculosis of spine

- Scotomy - Dizziness, nausea and dimness of sight

- Scrivener's palsy - Writer's cramp

- Shingles - Viral disease with skin blisters

- Softening of brain - Result of stroke or hemorrhage in the brain, with an end result of the tissue softening in that area

- Spanish Influenza - Epidemic influenza

- Spasms - Sudden involuntary contraction of muscle or group of muscles, like a convulsion

- Spina Bifida - Deformity of spine

- St. Vitus’ Dance - Ceaseless occurrence of rapid complex jerking movements performed involuntarily

- Stranger's Fever (also Yellow Jacket or Bronze John) - Yellow fever

- Swamp Sickness - Could be malaria, typhoid or encephalitis

- Thrombosis - Blood clot inside blood vessel

- Thrush - Childhood disease characterized by spots on mouth, lips and throat

- Toxemia of Pregnancy - Eclampsia

- Variola - Smallpox

- Viper's Dance - St. Vitus Dance