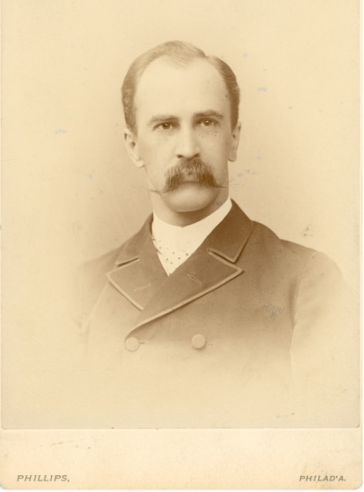

William Osler was born in Bond Head (southwestern Ontario) Canada in 1849. His father Featherstone Lake Osler was a former lieutenant in the Royal Navy who was invited to serve as a science officer on the HMS Beagle for Darwin’s voyage to Galapagos. Instead he became a minister of the Church of England. In 1867 William entered Trinity College in Toronto fulfilling his mother’s wishes for him to follow in his father’s footsteps into the Anglican priesthood. A year later however he enrolled in the Toronto School of Medicine before transferring to the McGill University Faculty of Medicine from which he received his medical degree in 1872. McGill offered a 4-year curriculum and access to better clinical facilities at Montreal General Hospital. Following medical school Osler embarked on an 18-month tour of the laboratories and clinics in Europe. Osler spent 3 months in Berlin working with the great pathologist Rudolph Virchow. He returned to Canada in 1874 and briefly engaged in a general practice before joining the faculty at McGill as an instructor in biology, physiology and pathology. In 1878 he became an attending physician at Montreal General Hospital where he introduced bedside clinical teaching on his ward. In addition to his teaching, he performed over 1,000 autopsies at Montreal General Hospital, introduced the first course in clinical microscopy in Canada, established McGill’s first physiology laboratory and volunteered to take charge of the smallpox wards for his willing colleagues.

William Osler was born in Bond Head (southwestern Ontario) Canada in 1849. His father Featherstone Lake Osler was a former lieutenant in the Royal Navy who was invited to serve as a science officer on the HMS Beagle for Darwin’s voyage to Galapagos. Instead he became a minister of the Church of England. In 1867 William entered Trinity College in Toronto fulfilling his mother’s wishes for him to follow in his father’s footsteps into the Anglican priesthood. A year later however he enrolled in the Toronto School of Medicine before transferring to the McGill University Faculty of Medicine from which he received his medical degree in 1872. McGill offered a 4-year curriculum and access to better clinical facilities at Montreal General Hospital. Following medical school Osler embarked on an 18-month tour of the laboratories and clinics in Europe. Osler spent 3 months in Berlin working with the great pathologist Rudolph Virchow. He returned to Canada in 1874 and briefly engaged in a general practice before joining the faculty at McGill as an instructor in biology, physiology and pathology. In 1878 he became an attending physician at Montreal General Hospital where he introduced bedside clinical teaching on his ward. In addition to his teaching, he performed over 1,000 autopsies at Montreal General Hospital, introduced the first course in clinical microscopy in Canada, established McGill’s first physiology laboratory and volunteered to take charge of the smallpox wards for his willing colleagues.

Medical education at the time at the University of Pennsylvania was divided into two tiers that separated the University and hospital faculty. Professors were involved in the preclinical subjects including anatomy, pathology, materia medica and pharmacy. The title Clinical professor reflected the hospital hierarchy. In 1875 the entire University of Pennsylvania had 43 professors including 9 from the medical school who served with full faculty voting privileges. In 1875 the Board of Trustees created 3 new clinical professorships in the hospital including one for diseases of the nervous system. Horatio C. Wood, a pharmacologist with a position in the botany department had been appointed a lecturer in nervous diseases when the Department of Neurology was established in 1871. Wood was appointed clinical professor in nervous diseases in 1875 and the following year elected to a full university chair as Professor of Materia Medica and Pharmacy. In 1884 William Pepper, Jr. who was already provost of the University of Pennsylvania became chair of the theory and practice of medicine leaving vacant the professorship of clinical medicine at Penn. Until that point, with almost no exceptions, the University of Pennsylvania had only appointed medical chairs who were graduates of the University or native Pennsylvanians, usually both. Horatio C. Wood traveled to Montreal to check on Osler and returned to Philadelphia with enthusiastic reports. S. Weir Mitchell, eminent physiologist and neurologist and now a trustee of the University, was given the mission to meet and interview Osler in London. Mitchell was so impressed that he cabled the trustees the next morning, “Alright! Elect Osler.” When Osler left Montreal in 1884 the McGill medical students, sorry to see Osler leave Montreal, walked with him to the railroad station.

1f11William Osler arrived in Philadelphia on Saturday afternoon October 11, 1884 and stayed at the Aldine Hotel at 1918-20 Chestnut Street. The hotel had formerly been the suburban home of the son of Benjamin Rush but was transformed into a boarding house by Lippincott, the publisher, for the 1876 Centennial Exposition. (Later visitors to the hotel included Ty Cobb and Babe Ruth). D. Hayes Agnew, the first John Rhea Barton professor of surgery at the University of Pennsylvania invited “Dr. and Mrs. Osler” to share his pew at the Second Presbyterian Church the following Sunday. When Osler arrived unaccompanied, Agnew whispered regrets that he was alone. Osler, known for his mischievous demeanor, raised his eyebrows and gestured with his finger which Agnew interpreted that his wife was expecting. (While in Philadelphia Osler invented his alter ego “Egerton Yorrick Davis” – purported to be a retired US Army surgeon living in Caughnawaga, Quebec. Under the Davis pseudonym, Osler fooled the editors of the Philadelphia Medical News to publish the extremely rare phenomenon of penis captivus in 1884 and in 1902 a case report of Peyronie’s disease in which an “old codger of 65 years” presents with strabisme du penis). Ten days after arriving in Philadelphia the bachelor Osler moved into a 3 story brick house at 131 S. 15th Street. The front room was a book lined office. Upstairs resided a caterer who provided Osler with breakfast and tended to his simple needs. Osler’s diary entries in 1884 included invitations for dinner with notable neurologists Wharton Sinkler on October 28 and Weir Mitchell on November 23. At the time Mitchell was president of the Philadelphia Neurological Society which Osler joined in January 1885. On November 2 he dined with Dr. Samuel W. Gross, professor of surgery at Jefferson, and his wife Grace Revere Gross. Mrs. Gross was the great-granddaughter of Paul Revere. (Osler became close friends with the Gross’ while in Philadelphia and later married Grace Revere in 1892 three years after her husband’s death).

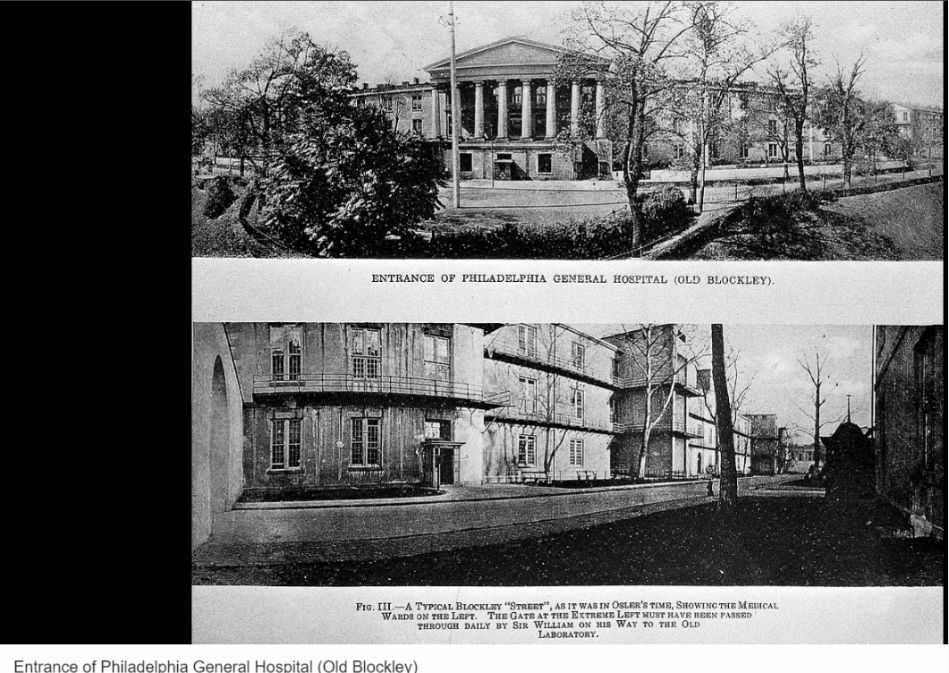

![]() At the time that Osler arrived, medical education at the University of Pennsylvania was undergoing radical changes. Following the reforms at Harvard a few years earlier, a three-year medical course became mandatory. The senior class of 1884 was the first for whom an entrance examination had been required. With the exception of Joseph Leidy, professor of anatomy – all of the faculty maintained active private practices for which their university position served as a portal of entry. They held afternoon office hours and made house calls. Osler however was disinclined towards general practice limiting himself to occasional consultations. He shared 2 large wards at the University hospital with William Pepper who was head of the medical department. Pepper however was also provost of the University and maintained a large private practice. Pepper rarely appeared except to give his standard lectures so Osler had the wards to himself surrounded by increasing numbers of enthusiastic students. Osler wrote “Medicine is learned by the bedside and not in the classroom. Let not your conceptions of disease come from word heard in the lecture room or read from a book. See, and then reason and compare and control. But see first.” Soon after his arrival in Philadelphia, Osler was appointed pathologist at Philadelphia General Hospital (“Old Blockley” – named for the township of Blockley on the west side of the Schuylkill River to which the Philadelphia Almshouse had moved in 1834). Even in Osler’s time the hospital held over 2,000 residents including the indigent poor, alcoholics and the insane. After spending the morning at the University Hospital, Osler would leave by a rear door and due to the proximity of the two institutions enter Old Blockley thru a gate nearby to which a small red brick building stood. There he performed at least 162 autopsies including brain cutting. Sometimes he would start a post-mortem exam at 8 am and work into the evening. If he found something particularly interesting he would send a runner to summon all of the “boys” to show what a wonderful thing, he had found.

At the time that Osler arrived, medical education at the University of Pennsylvania was undergoing radical changes. Following the reforms at Harvard a few years earlier, a three-year medical course became mandatory. The senior class of 1884 was the first for whom an entrance examination had been required. With the exception of Joseph Leidy, professor of anatomy – all of the faculty maintained active private practices for which their university position served as a portal of entry. They held afternoon office hours and made house calls. Osler however was disinclined towards general practice limiting himself to occasional consultations. He shared 2 large wards at the University hospital with William Pepper who was head of the medical department. Pepper however was also provost of the University and maintained a large private practice. Pepper rarely appeared except to give his standard lectures so Osler had the wards to himself surrounded by increasing numbers of enthusiastic students. Osler wrote “Medicine is learned by the bedside and not in the classroom. Let not your conceptions of disease come from word heard in the lecture room or read from a book. See, and then reason and compare and control. But see first.” Soon after his arrival in Philadelphia, Osler was appointed pathologist at Philadelphia General Hospital (“Old Blockley” – named for the township of Blockley on the west side of the Schuylkill River to which the Philadelphia Almshouse had moved in 1834). Even in Osler’s time the hospital held over 2,000 residents including the indigent poor, alcoholics and the insane. After spending the morning at the University Hospital, Osler would leave by a rear door and due to the proximity of the two institutions enter Old Blockley thru a gate nearby to which a small red brick building stood. There he performed at least 162 autopsies including brain cutting. Sometimes he would start a post-mortem exam at 8 am and work into the evening. If he found something particularly interesting he would send a runner to summon all of the “boys” to show what a wonderful thing, he had found.

In addition to his teaching responsibilities, work in the morgue and consultations, Osler was appointed to the staff of the Philadelphia Orthopedic Hospital and Infirmary for Nervous Disease in January 1885.

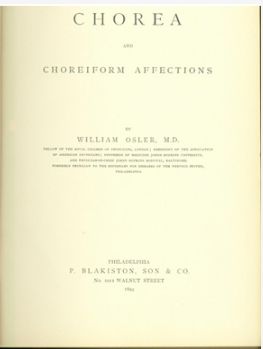

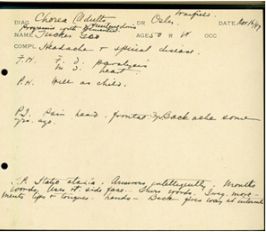

In addition to his teaching responsibilities, work in the morgue and consultations, Osler was appointed to the staff of the Philadelphia Orthopedic Hospital and Infirmary for Nervous Disease in January 1885.  Afternoon clinics at the infirmary were divided between Mitchell, Sinkler and Osler. He saw his first patient at the infirmary on January 21, 1885 – a 12-year-old girl with chorea. As physician to the infirmary Osler saw at least 735 patients with a broad spectrum of diseases including cerebral palsy, chorea, ataxia, subdural hematoma, brain tumor, spinal cord disease, cerebral embolism, aneurysm and neurasthenia. Osler published a monograph The Cerebral Palsies of Children based on the experiences he, Sinkler and Mitchell had with 151 cases of cerebral palsy at the infirmary. Osler’s second neurological monograph On Chorea and Choreiform Affections was based on 410 patients seen at the infirmary. He presented his material on chorea at the meeting of the Canadian Medical Association in 1887 but the monograph was published later in 1894. Osler was elected a member of the American Neurological Association in 1888.

Afternoon clinics at the infirmary were divided between Mitchell, Sinkler and Osler. He saw his first patient at the infirmary on January 21, 1885 – a 12-year-old girl with chorea. As physician to the infirmary Osler saw at least 735 patients with a broad spectrum of diseases including cerebral palsy, chorea, ataxia, subdural hematoma, brain tumor, spinal cord disease, cerebral embolism, aneurysm and neurasthenia. Osler published a monograph The Cerebral Palsies of Children based on the experiences he, Sinkler and Mitchell had with 151 cases of cerebral palsy at the infirmary. Osler’s second neurological monograph On Chorea and Choreiform Affections was based on 410 patients seen at the infirmary. He presented his material on chorea at the meeting of the Canadian Medical Association in 1887 but the monograph was published later in 1894. Osler was elected a member of the American Neurological Association in 1888.

![]() William Osler’s bibliography included over 1400 papers, monographs and notes. It is estimated that he published something every 5 days! In particular Osler published close to 200 papers, reviews, editorials and monographs on neurological subjects. His earliest work including studies of the brains of two criminals compared to 34 normal controls at Montreal General Hospital refuting the claim that criminals’ brains had an extra horizontal frontal gyrus. He published on cerebral localization and described pure word blindness in 1891 the same year as Dejerine. While in Philadelphia he wrote a

William Osler’s bibliography included over 1400 papers, monographs and notes. It is estimated that he published something every 5 days! In particular Osler published close to 200 papers, reviews, editorials and monographs on neurological subjects. His earliest work including studies of the brains of two criminals compared to 34 normal controls at Montreal General Hospital refuting the claim that criminals’ brains had an extra horizontal frontal gyrus. He published on cerebral localization and described pure word blindness in 1891 the same year as Dejerine. While in Philadelphia he wrote a  paper on subdural hematoma taking issue with the commonly held notion attributed to Virchow that the etiology was inflammatory (pachymeningitis hemorrhagica). He was one of the first to describe a clot in the middle cerebral artery and the first to describe a mycotic aneurysm in bacterial endocarditis. Osler described arsenical neuropathy and probably what was Guillain-Barre Syndrome in post-typhoid neuropathy. He visited a nephew in Toronto who had developed an acute paralysis and discussed the differential diagnosis of polyneuritis v poliomyelitis noting sensory changes and better prognosis in polyneuritis. He described the first MS case in Canada at autopsy in 1881.

paper on subdural hematoma taking issue with the commonly held notion attributed to Virchow that the etiology was inflammatory (pachymeningitis hemorrhagica). He was one of the first to describe a clot in the middle cerebral artery and the first to describe a mycotic aneurysm in bacterial endocarditis. Osler described arsenical neuropathy and probably what was Guillain-Barre Syndrome in post-typhoid neuropathy. He visited a nephew in Toronto who had developed an acute paralysis and discussed the differential diagnosis of polyneuritis v poliomyelitis noting sensory changes and better prognosis in polyneuritis. He described the first MS case in Canada at autopsy in 1881.

The graduation ceremony for the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine took place on May 1, 1889. William Pepper, professor of medicine and the provost of the University presided. The ceremony marked the retirement of D. Hayes Agnew as professor of surgery and the undergraduate medical classes had commissioned noted Philadelphia artist Thomas Eakins to paint the Agnew Clinic for the bargain sum of $750. The painting was accepted on behalf of the University by Weir Mitchell, member of the Board of Trustees. The graduating class chose William Osler to give the valedictory address. Osler’s famous address “Aequanimitas” extolled the 2 virtues of imperturbability and equanimity – virtues that would “make or mar” the lives of the graduates. He concluded his address with the surprise announcement that he was leaving the University of Pennsylvania to be one of the four founders of the Johns Hopkins Hospital, “One might have thought that in the premier school of America, in this Civitas Hippocratica, with associations so dear to a lover of his profession, with colleagues so distinguished, and with students so considerate, one might have thought, I say, that the Hercules Pillars of a man’s ambition had here been reached. But it has not been so ordained, and to-day I sever my connexion with this University. More than once, gentlemen, in a life rich in the priceless blessings of friends, I have been placed in positions in which no words could express the feelings of my heart, and so it is with me now. The keenest sentiments of gratitude well up from my innermost being at the thought of the kindliness and goodness which have followed me at every step during the past five years. A stranger – I cannot say an alien – among you, I have been made to feel at home – more you could not have done. Could I say more? Whatever the future may have in store of success or of trials, nothing can blot the memory of the happy days I have spent in this city, and nothing can quench the pride I shall always feel at having been associated, even for a time, with a Faculty so notable in the past, so distinguished in the present, as that from which I now part. Gentlemen, - Farewell, and take with you into the struggle the watchword of the good old Roman – Aequanimitas.”

William Osler left the University of Pennsylvania in 1889 for the new Johns Hopkins Hospital and medical school. In 1905 he was offered the professorship of medicine at Oxford. His wife Grace Revere Osler cabled him, “Do not procrastinate, accept at once. Better go in a steamer than in a pine box.” Osler continued his illustrious career at Oxford and was created a baronet by King George V in 1911. His only surviving son Revere was killed while serving in the British army in 1917, an event that Osler never recovered from. Sir William Osler died at Oxford in 1919 from pneumonia and empyema. He once said, “I desire no other epitaph than the statement that I taught medical students in the wards, as I regard this as by far the most useful and important work I have been called upon to do.”