MD-PhD Student-to-Student Guide on Choosing Rotation/Thesis Mentors and Navigating the Dissertation

Faculty Director Introduction

Here are some things to think about as you work your way through the process of picking a thesis mentor and completing your thesis. Some of these points came up during the recent "Navigating through the thesis years" session. Others are questions that are frequently asked in one-on-one sessions. This list was written with combined degree students in mind, but most of the issues are generic. The idea is that you are doing a thesis project to prepare you for a career as a physician-investigator. Your training for that role began before you got to Penn and will continue after you leave the MD-PhD program. This is a step, not the entire journey - but it is an important step. It is also one of those rare times that you will be able to focus on a research project with a minimum of other distractions and competing pressures. Make sure that you are selecting a thesis mentor and joining a research team that will contribute to your training in a positive way. Depending on your graduate program, that team may function in a lab environment (wet or dry) or it may be a very different setting, especially for those of you who are social scientists. Whatever the setting, your goal in the graduate school phase of the MD/PhD program should be to acquire valuable skills that will help you identify important problems, reduce them to testable hypotheses, gather data, come to defensible conclusions and share them with the world.

- Skip Brass

Student Authors Introduction

This guide was assembled by Ruth Choa and Jacob Sterling with input from Lawrence Brass, Maggie Krall, Rahul Kohli and Aimee Payne. It is written from the perspective of an MSTP candidate in a BGS PhD program, but the principles apply to bioengineering and all other graduate programs associated with the MSTP even if the details may vary considerably.

- Ruth Choa & Jacob Sterling

When should I start thinking about research rotations?

Selecting research rotation advisors can seem like a daunting task, particularly while you are busy with medical and graduate school coursework. There are many faculty members Penn and many of them will be doing research that sounds interesting. Deadlines for choosing faculty mentors (including the MS1 spring independent study) can easily sneak up on you. Our recommendation is to start building a list of potential research mentors in September of MS1. This will provide ample time to undertake the steps below.

What is the purpose of doing research rotations?

The primary goals of a research rotation are to (1) identify your PhD advisor and (2) learn something new. We recommend using the framework below to first identify labs of interest and then narrow that list.

By using the framework below, you may be able to narrow your selection to a single lab/PI without completing the required number of rotations for your graduate group. If this is the case, you can use your remaining required rotations to learn new techniques or establish a collaboration. These secondary goals should only be considered once you have selected a thesis lab and it has been approved by both your graduate group and the MSTP office. Any additional rotations to achieve these secondary goals should be discussed at length with your future PhD advisor to maximize your learning.

How can I identify PhD advisors/potential research rotations?

- Create the initial list of ~5 candidates using the following resources:

- Graduate Group Website

- MSTP Faculty Website

- Encounters in medical and graduate school classes (TiMM may be particularly helpful)

- Publications that caught your eye

- Mini-Talks, Seminars, Research in Progress Talks by students and faculty

- Direct and indirect encounters with faculty at graduate group and MSTP events (e.g. the annual MSTP retreat)

- Note: Faculty on your list should be members of your graduate group, but your graduate group chair may allow you to rotate with faculty outside the group.

- Narrow the list using the following data (but understand that steps to “narrow the list” may also lead to the discovery of new names to consider). Talk to advisors, peers, and the PI themselves! Reach out to the following individuals and set up time to discuss your list:

- Graduate group chair

- MSTP/Graduate group advisor

- MSTP Director, Dr. Brass

- Former/current students in that lab (ask Maggie to connect you)

- The PI themselves

- Rotate in the lab!

Don’t forget that your choices will need to be approved by both your graduate group chair and the MSTP director. This can be initiated with an email, but either or both may wish to meet to discuss your choice. Thoughtful choices for rotation PI and thesis advisor are almost always approved. Reasons that may keep your choices from being approved include concerns about the productivity of the lab, poor experiences for previous students, concerns that too many graduate students are joining the lab at the same time, lack of resources in the lab and impending departure of the faculty member from Penn.

Can I work with junior faculty members?

Selection of a junior faculty member who has not had a graduate student and/or has not yet received R level funding from the NIH (or equivalent) means that you will need a thesis coach or senior co-mentor for your thesis. Coaches and co-mentors are not required for rotations.

How many lab rotations should I do?

The number of required rotations is set by the graduate group. If you’ve found the right lab before meeting the requirement you should discuss it with your graduate group chair and your future thesis advisor. Options include using the additional rotations to achieve secondary goals as outlined above or having the requirement for additional rotations waived. Ultimately this decision is made by the graduate group, not the MSTP.

What are the goals of doing a doctoral thesis?

Learning how to start from an observation and build an entire project from that observation - this includes asking critical and significant questions, coming up with hypotheses, designing and executing experiments, analyzing data, making conclusions, and communicating those results in both the written and oral forms to different audiences. The overarching goal is to develop the skills that will help you become an independent physician-scientist. Additionally, you should also develop a broad understanding of your scientific discipline from your coursework and seminars – the added value of a PhD versus just doing a postdoc.

When should I start my thesis research?

This is usually sometime in the spring of third year (first year of graduate school) or beginning of fourth year (second year of graduate school). Some people start their thesis research as early as during their lab rotations, others end up working on a different project than their rotation project and so start their thesis research a bit later. Technically, you are an official “thesis research student” once you pass your preliminary exam, but most people will work on their thesis research prior to that. Don’t hesitate to dive in! Some very successful MD/PhD students have managed a relatively short time to degree by initiating the project that became their thesis during Year 1 of the program.

What is the best topic for a thesis? Should it be “safe”? Should it be risky?

Pick a project that you are passionate about. Think about its impact and whether your results will be significant to you and your field. Graduate school can be tough! You want to spend your thesis years working on something that is meaningful to you. It is also never too early to develop the habit of picking impactful problems since impact is one of the criteria used by NIH study sections when deciding whether a proposal should be funded.

You should balance safety with risk-taking. Often, projects end up taking unexpected turns, so it is better not to place all your eggs in one basket at first. If you want to work on a risky project, it may be beneficial to start your thesis research working on a couple projects at first – a “low hanging fruit” safety project that has good chances of success, as well as the riskier project. Then, as you generate data and have a clearer direction of the projects, you can decide how to distribute your thesis research time between the two.

Getting a project off the ground and running is the hardest part of doing a PhD! If you are consistently getting only negative data and are struggling to decide whether a project is worth continuing to pursue, you should have serious conversations with your PI regarding whether to switch projects. Along those lines, discussing with your PI early how to design robust rule in/rule out experiments can save you months if not years of work, as can discussions with your thesis committee. Knowing when to drop vs. continue a project is a key to thesis research success. It is rarely a good idea to be fruitlessly pursuing even the most attractive hypothesis for more than about 8 months without compelling reasons to do so.

Remember: standing on the shoulders of giants may not always give you the best viewpoint! It is not at all unusual for projects to be built on prior work done by others. Sometimes this means building off work done by other research groups or others in your lab. Keep in mind that those previous observations may prove to be mistaken, even if they have been published. This does not mean that there has been scientific misconduct, although that can happen. It does mean that you should have frank discussions with your thesis advisor and thesis committee if you are unable to move a project forward that is based on someone else’s work. If you feel your concerns are not being adequately addressed, talk to your graduate group chair and/or the MSTP director. Don’t spend months fruitlessly trying to reproduce someone else’s observations while blaming yourself for not being able to do that.

Should I pick a project in an area that I want to work on for the rest of my career?

If you know exactly what you want to work on for your future career, there is no downside to working on a project in that area. Chances are though, your career interests will almost certainly change as you progress through medical school, residency, fellowship, etc. The goal of graduate school is to learn how to think scientifically and be able to apply those problem-solving skills to new questions in the future. Pick a project that you care about currently, and don’t worry as much about whether it necessarily matches with your future clinical or career plans.

How long should it take?

As long as it takes to achieve the goals of PhD and produce an identifiable body of work. Most MD/PhD students spend 3-5 years in graduate school, taking 8 years on average for the entire MD/PhD program. You should discuss with your PI what your individual goals are for your PhD early on, and then re-evaluate each year with your PI where you are towards achieving those goals and whether to adjust those goals. Make sure that you and your thesis advisors have aligned expectations!

Who decides when I’m done?

Your thesis committee along with your PI. The decision is usually based on their assessment of whether you have mastered your field, achieved the goals of your PhD, and made a scholarly contribution to the field.

How many publications will I need to have?

This is grad group dependent, but the MSTP rules require at least 1 first author paper and most grad groups require 1-2 first author papers. You should aim to publish or have your papers accepted before you defend and return to medical school. It is possible to finish paper revisions while being back in medical school, but most find it to be very challenging. Note that in a recent survey, physician-scientist friendly residency directors said that having at least one first author paper from thesis research is something on which they put a great deal of weight.

Should I work in a big lab or a small lab?

This depends on individual preference, there are pros and cons to both. In a big lab you may get greater exposure to different projects while in a small lab you may get more hands-on mentorship. Make sure either way that the training you get is solid and will help you achieve your PhD goals. You should talk to other students in the lab, including any previous MD/PhD students. Maggie can tell you if another MD/PhD student has done their thesis with that faculty member before, but keep in mind that there are also faculty who would be terrific thesis advisors for an MD/PhD student but have not yet had a chance to do that. MD/PhD students often have a slightly more accelerated graduate school timetable, so you want to make sure your PI is familiar with the MD/PhD training process.

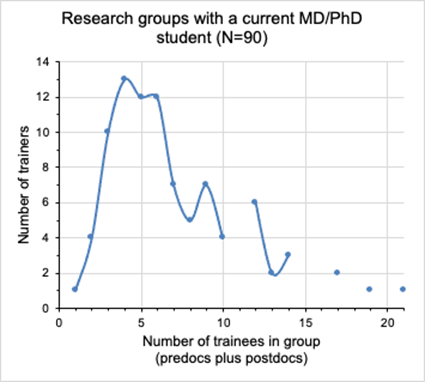

The following graph gives a sense of lab group sizes of the 90 MSTP training faculty members who currently have an MD/PhD thesis student using “predocs plus postdocs” as a surrogate marker. This doesn’t include undergraduates, staff scientists, technicians, etc.

Should my thesis advisor be a physician-scientist or a scientist?

Either is fine as long as s/he is successful. The data below shows the degree(s) and academic rank of the 90 MSTP training faculty members who currently have an MD/PhD thesis student as of December 2021. If your thesis advisor is a physician-scientist, take advantage of their perspective as a physician-scientist. If your thesis advisor is a scientist, but not a physician-scientist, be sure to have at least one physician-scientist on your thesis committee.

Distribution of degree(s) among thesis mentors

MD/PhD 28%

VMD/PhD 1%

PhD 61%

MD or VMD 10%

Total 100%

Distribution of academic rank among thesis mentors

Assistant Professor 18%

Associate Professor 26%

Professor 57%

Total 100%

Is it OK to do my thesis with a junior faculty member?

Yes. Working with a junior faculty member can be beneficial because they may be around the lab more. However, they may also have less experience in being a mentor than senior faculty. You should discuss the issue of tenure with them – this comes up at around 5 years for faculty without clinical responsibilities, and at around 8 years for faculty with clinical responsibilities. You want to make sure that you have a plan in the worst-case scenario that a junior faculty PI fails to earn tenure and leaves the school. Selection of a junior faculty member who has not had a graduate student and/or has not yet received R level funding from the NIH (or equivalent) means that you will need a thesis coach or senior co-mentor for your thesis. Coaches and co-mentors are not required for rotations.

How often should I expect to meet with my thesis advisor?

This varies depending on the lab and the mentorship style of your advisor. Some advisors have students set up weekly meetings to discuss progress while other advisors have an open-door policy and may talk to their students every day. You should aim to talk with your advisor at least once per week, preferably in a one-on-one setting. You should also discuss mentorship style and frequency of meetings with your PI prior to joining a lab. Two useful points about good mentorship apply here. First, be sure that your expectations and your prospective thesis advisor’s expectations are well aligned before you begin. Second, make effective use of scheduled meeting times with your thesis advisor. Go into meetings knowing what you want to talk about with them and how you want them to help you. In other words, have an agenda and be efficient.

What is the purpose of having a thesis advisor?

To help you develop as a researcher and grow in scientific independence! Your thesis advisor will play an important role for the rest of your career so you want to pick someone who you really feel will be supportive of you and your career goals. All thesis advisor choices need be approved by Skip and your graduate group leader.

Can I do my thesis with a faculty member outside my graduate group?

This varies depending on the graduate group. Most graduate groups prefer that your faculty member be in the group but may be willing to add the faculty member to the group – you should talk to your grad group leader about it. Often this discussion will take place before your rotate, with a plan for the PI to be added the graduate group if you both decide to work together. If your PI is able to be added to your graduate group, s/he may need to undergo additional training regarding grad group specific mentor expectations, preliminary exam processes, or other thesis research requirements.

Can I do my thesis with a faculty member at another university?

No. The only exceptions are if your PI moves to another institution during your PhD (in which case you will have to make a difficult decision regarding whether to switch PIs or move with your PI, depending on where you are in your thesis research) and the NIH-affiliated Penn program for students in the Immunology graduate group.

Who supports me financially while I’m doing my thesis?

Mostly your thesis advisor, so be sure to discuss whether their lab has adequate funding before you join. Other options include training grants (ex. T32) or individual fellowships (ex. F30/F31).

What is the purpose of my thesis committee?

The thesis committee serves multiple purposes outlined below:

- Oversee PhD Progress - As a graduate student you will have thesis committee meetings every 6 months to review your data and ensure that you are making adequate progress towards a successful defense. In addition to data production, your committee will also oversee the development of skills necessary to become an independent investigator, including hypothesis generation, grant writing, collaboration, data interpretation, and scientific communication. Based on your data production and skill development your committee will determine when you have done enough to earn your PhD by giving you permission to defend.

- Guide Your Research - At thesis committee meetings, members will interrogate your data and conclusions with the goal of strengthening your story and identifying potential weaknesses before submission to a journal or your defense date. They may also help you and your advisor focus your future experiments on the avenues they view as most impactful or fruitful.

- Mentorship - The thesis committee is also a set of mentors that you and your advisor have selected. These mentors can serve a variety of different purposes including:

- Intellectual mentorship, helping to steer the project or provide information on a particular topic area

- Technical mentorship in a particular technique

- Clinical mentorship for those who may have already chosen their clinical field early and are doing relevant dissertation work. In these cases, a committee member might be able to help identify clinical correlates for your research to maximize translational impact and eventually support a residency application in your field of choice. Note that many students do not choose a clinical field until much later in the program, and that’s definitely fine too.

- Conflict Mediation - The committee can, if necessary, also serve as a counterbalance to your thesis advisor. See sections below on thesis committee chair selection for more information.

How often should I meet with my thesis committee?

The MSTP requires thesis committee meetings at least every 6 months (can be less than 6 months if the committee requests meetings more often). In the BGS graduate groups, the first meeting should be no later than 6 months after you pass your prelim exam. Meetings are generally scheduled for 1.5-2 hours. You should email Maggie and your Graduate Group Coordinator every time you have a committee meeting. Note that the “no more than 6 months apart” rule applies in the MSTP even if 1) the grad group is willing to let them be farther apart and 2) you feel like you have nothing new to tell them because nothing is working. Let Skip know if your committee asks you to break this rule.

In terms of actually scheduling the meeting, we recommend using when2meet.com.

When is the best time to schedule my next committee meeting?

Early, early, early. PIs are notoriously difficult to schedule. Scheduling multiple PIs for a single time can be excruciating. Do not wait for your paper to be accepted. Do not wait because you feel like you haven't made any progress. You should generally start the scheduling process within a week after your last committee meeting.

Who should be on my thesis committee?

Each graduate group has guidance on the number of committee members you will need and whether you will need an external reviewer (a PI from another institution) to join your committee.

As to the composition, the thesis committee is a unique opportunity to choose your own mentors (see “mentorship” under “What is the purpose of my thesis committee?” above). Mentorship cannot happen without communication. Therefore we stress choosing committee members you feel comfortable reaching out to for help. That can be technical assistance with an experiment, intellectual assistance working through a hypothesis or designing an experiment, support for your residency application (if they are MDs or MD/PhD) by writing letters on your behalf, reaching out to colleagues (and providing you with networking opportunities), or general support for any personal or professional challenges you face as a student. Ultimately these benefits can only be realized if you reach out to them, so choose committee members you can grow to rely on and feel comfortable communicating with directly.

In addition to mentoring, committee members can also serve as a counterweight to your thesis mentor(s) (see section below on “Who should chair my thesis committee?” for more detail). To that end it may serve the student’s interest to include an MSTP steering committee member on their thesis committee if their PI and/or committee lacks experience working with MD-PhD students.

On a practical note, consider scheduling when choosing committee members. If someone is difficult to schedule for a simple one on one meeting with you, has a ton of graduate students, or existing committee commitments, they will likely be a limiting factor when it comes to scheduling. One such person on a committee may be doable, but should generally be avoided if possible.

Who should chair my thesis committee?

The choice of committee chair is an incredibly important decision and should be done explicitly in advance of the first meeting. Do not leave this decision until the meeting itself. Once you have identified a potential chair, reach out to them directly and ask if they are willing to serve as the committee chair.

Ideally the chair is an experienced, senior faculty member who has experience as a PhD advisor and committee member. This person should be willing to invest in your education by taking an active role in mentoring you. This requires a significant amount of their time. In a previous section (“mentorship” under “What is the purpose of my thesis committee?”), we mention the committee as a counterbalance to your PI. Truly, it is the chair who is the counterbalance. An experienced chair, who occupies a senior role in the department will be a stronger advocate for you, than a younger, less experienced investigator who may avoid challenging your PI’s judgement. While this hopefully does not apply to your experience, there are certainly cases where a chair has to intervene on a student’s behalf with regards to the duration or focus of the project.

In general you should also consider the following:

- Have they served on MD-PhD committees/are they an MD-PhD themselves?

- Familiar with the MD-PhD timeline between meetings. (e.g. Have appropriate expectations for 6 months of data vs 12 months for PhD students.)

- Familiar with the MD-PhD timeline to graduation.

- What is the chair’s record of graduating students?

- Time to degree

- Previous students’ views

- Is this person going to make time for me/have time to mentor me and serve on this committee?

Finally, be upfront about your goals for your own thesis and ensure that your chair’s views align with your own. This can include parameters such as time to graduation, number of first-author manuscripts, and prestige of the journals in which your work will be published.

What should happen before each thesis committee meeting?

Each graduate group has specific requirements for committee meetings. Most, if not all, have a required written component alongside the presentation. Be organized. View every thesis committee meeting as an opportunity to get valuable input from a group of investigators that you have selected. In general you should plan a 30 minute talk that starts off with a brief reminder of how far along you are in the program, the goals of your project and highlights of your progress so far (papers, conferences, etc). You can then present your data highlighting any problems you’d like help with (technical, experimental design or interpretive in nature) before wrapping up with your plans for the next 6 months. Have an agenda so that you (and they) will have a better chance of accomplishing everything you need during your time with them. Always prioritize the points that are most important to you. Leading off with a secondary issue may mean that you never get to discuss the primary issue(s) that you most want their input on.

What should happen after each thesis committee meeting?

After your meeting your committee chair will submit a written report to you, your advisor, and the graduate group. The report is based on the consensus view of your committee. As a student, it is helpful to review this report with your committee chair after each meeting to ensure that you understand its contents.

Is it true that I can only return to medical school at certain times of the year?

No, students can return to medical school at any time throughout the year. However, for each student there will be certain times that are more or less optimal. Visit the Final Two Years of the Program page for more information.

If I’m uncertain about my clinical interests, is there anything I can do to help while I’m still in my thesis lab?

Yes. Take advantage of the Clinical Connections program. Attend the information sessions the program holds annually for some of the more popular clinical fields if those are of interest (Medicine, Pediatrics, Neurology, Pathology, Ophthalmology). Meet with your CD Program Advisor for advice and/or set up an appointment with Maggie to discuss the pros and cons of different fields. Set up appointments with key faculty members in areas of interest to you to discuss your career goals and seek their advice. Just an hour or two a week networking or participating in Clinical Connections can help you narrow down the best possibilities for you and minimize the anxiety of returning to the clinics. Keep in mind that there are advantages to selecting a clinical area in which physician-investigators are a well-established career model. If you intend to be a laboratory investigator, choose a field where any future clinical responsibilities will fit comfortably with the time you will spend doing research.

Do I really have to defend my thesis before going back to finish medical school?

Yes. In fact, you need the program director's permission to do otherwise. Why? Because the pressures to focus on completing your clinical education are great, the hours are long and the opportunities to devote thoughtful time to the completion of your project, the composition of your thesis and your public defense are minimal. If you encountered unexpected obstacles or delays, you would likely then leave the program with only your MD, despite having completed 90+% of the PhD. It’s not worth taking the risk of never being able to finish.