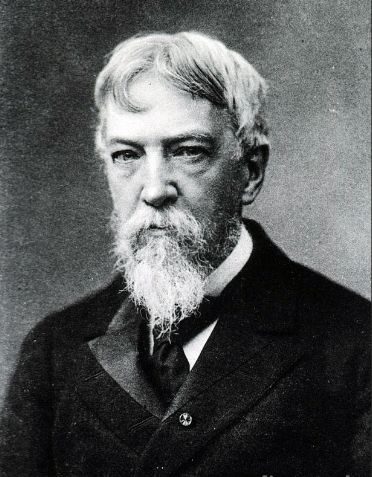

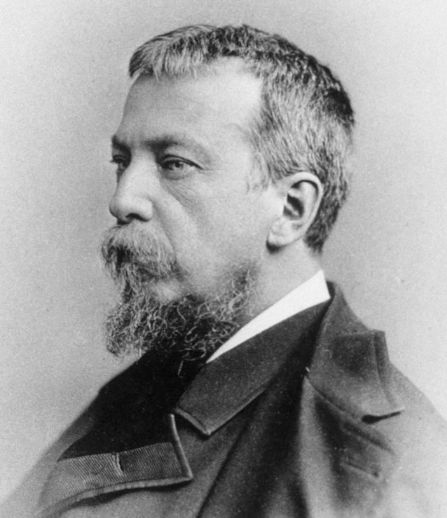

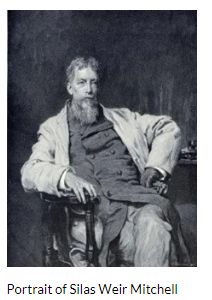

Silas Weir Mitchell was born the third of nine children to a family of physicians in Philadelphia. He was the 7th physician in 3 generations in his family. His father John Kearsley Mitchell was a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine and professor of the theory and practice of medicine at Jefferson Medical College. J.K. Mitchell had a serious interest in and taught chemistry at the Franklin Institute while maintaining a practice of medicine. Weir Mitchell (he did not use his first name) entered the University of Pennsylvania at age 15. He was said to be a distracted student - writing too much poetry and playing too much billiards. He dropped out of Penn after 3 years to help his ailing father in his medical practice. He resumed his education at Jefferson Medical College in 1848. When he announced his plans to study medicine, his father told him, "you are wanting in nearly all of the qualities that go to make a success in medicine. You have brains, but no industry." While at Jefferson, Mitchell worked as a student assistant in the laboratory of Robley Dunglison, America's leading physiologist. In spite of his father's prediction he graduated Jefferson in 1850 at the age of 21. After graduation Mitchell and his sister Elizabeth travelled to Paris where he took courses with Claude Bernard in physiology and Charles Robin in microscopy. When discussing a hypothesis with the great physiologist Bernard, Mitchell stated that "I think that so and so must be the case." Bernard replied "Why think, when you can experiment? Exhaust, experiment and then think." Mitchell's European tour was cut short due to his father's illness. He was denied a residency at Pennsylvania Hospital purportedly due to his father's politics. He joined his father's medical practice and assumed it completely after his death in 1858. During the years he worked in his father's practice he also worked after hours in the laboratory. In 1853 he was elected to the Academy of Natural Sciences. His laboratory research included studying the effects of rattlesnake venoms in collaboration with physiologist William Alexander Hammond with whom he developed a lasting friendship and collaboration. Following medical school Hammond spent a year's residency at Pennsylvania Hospital before being commissioned as an assistant surgeon in the U.S. Army. Together Mitchell and Hammond studied the mechanism of action and physiological effects of snake venoms and arrow poisons on a variety of animals and at times even themselves. Mitchell also studied the generation of uric acid, blood crystals of sturgeons and the circulation of snapping turtles. He also studied the emotional and physical effects in himself after ingesting the dried tops of the mescal cactus, a source of psilocybin.

Silas Weir Mitchell was born the third of nine children to a family of physicians in Philadelphia. He was the 7th physician in 3 generations in his family. His father John Kearsley Mitchell was a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine and professor of the theory and practice of medicine at Jefferson Medical College. J.K. Mitchell had a serious interest in and taught chemistry at the Franklin Institute while maintaining a practice of medicine. Weir Mitchell (he did not use his first name) entered the University of Pennsylvania at age 15. He was said to be a distracted student - writing too much poetry and playing too much billiards. He dropped out of Penn after 3 years to help his ailing father in his medical practice. He resumed his education at Jefferson Medical College in 1848. When he announced his plans to study medicine, his father told him, "you are wanting in nearly all of the qualities that go to make a success in medicine. You have brains, but no industry." While at Jefferson, Mitchell worked as a student assistant in the laboratory of Robley Dunglison, America's leading physiologist. In spite of his father's prediction he graduated Jefferson in 1850 at the age of 21. After graduation Mitchell and his sister Elizabeth travelled to Paris where he took courses with Claude Bernard in physiology and Charles Robin in microscopy. When discussing a hypothesis with the great physiologist Bernard, Mitchell stated that "I think that so and so must be the case." Bernard replied "Why think, when you can experiment? Exhaust, experiment and then think." Mitchell's European tour was cut short due to his father's illness. He was denied a residency at Pennsylvania Hospital purportedly due to his father's politics. He joined his father's medical practice and assumed it completely after his death in 1858. During the years he worked in his father's practice he also worked after hours in the laboratory. In 1853 he was elected to the Academy of Natural Sciences. His laboratory research included studying the effects of rattlesnake venoms in collaboration with physiologist William Alexander Hammond with whom he developed a lasting friendship and collaboration. Following medical school Hammond spent a year's residency at Pennsylvania Hospital before being commissioned as an assistant surgeon in the U.S. Army. Together Mitchell and Hammond studied the mechanism of action and physiological effects of snake venoms and arrow poisons on a variety of animals and at times even themselves. Mitchell also studied the generation of uric acid, blood crystals of sturgeons and the circulation of snapping turtles. He also studied the emotional and physical effects in himself after ingesting the dried tops of the mescal cactus, a source of psilocybin.

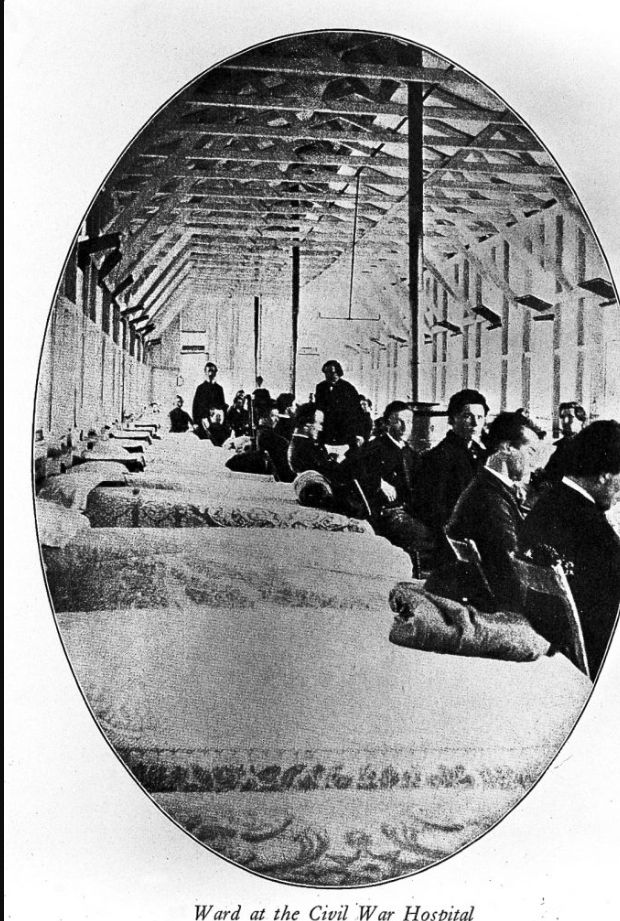

Medical life in Philadelphia was greatly disrupted by the Civil War. Both the University of Pennsylvania and Jefferson Medical College were institutions favored by southern medical students prior to the  War. Just before the Civil War, the Philadelphia medical schools enrolled 1200 students, about 650 came from below the Mason Dixon Line. The withdrawal of the southern students and the press of military service depleted the enrollment in Philadelphia's medical schools. By virtue of its geographic position and medical resources, Philadelphia played an important role in supporting the Union forces. Medical graduates of the University of Pennsylvania probably outnumbered any other school in the War. They made up 25% of the Confederate Army surgeons and 6% of the Union Army. By the spring of 1863 the army's need for assistant surgeons was so great that the faculty of the University persuaded the trustees to rescind the requirement of a year's clinical experience before receiving the MD degree.

War. Just before the Civil War, the Philadelphia medical schools enrolled 1200 students, about 650 came from below the Mason Dixon Line. The withdrawal of the southern students and the press of military service depleted the enrollment in Philadelphia's medical schools. By virtue of its geographic position and medical resources, Philadelphia played an important role in supporting the Union forces. Medical graduates of the University of Pennsylvania probably outnumbered any other school in the War. They made up 25% of the Confederate Army surgeons and 6% of the Union Army. By the spring of 1863 the army's need for assistant surgeons was so great that the faculty of the University persuaded the trustees to rescind the requirement of a year's clinical experience before receiving the MD degree.

Students went directly from the lecture room to the army just 4 months before the Battle of Gettysburg. Philadelphia, second only to Washington, became an important center for the care of the sick and wounded soldiers and sailors of the North. There were more than 14,000 hospital beds in the Philadelphia area and at the end of the war the U.S. Sanitary Commission reported that 157,00 soldiers and sailors had been treated in Philadelphia.

To avoid conscription and not wishing to leave his mother with the financial responsibility of the large Mitchell family, Weir Mitchell volunteered to serve as a contract surgeon locally at the Filbert Street Military Hospital. There he became impressed with the magnitude of the problem of peripheral nerve injuries. His friend and research collaborator William Hammond had resigned from the US Army in 1860 to take on the professorship of anatomy and physiology at the University of Maryland. With the outbreak of the Civil War, Hammond returned to the Army one year later. In 1862 at the age of 33 he was appointed Surgeon General by President Abraham Lincoln. (A feud with Secretary of War Stanton later led to Hammond's court-martial and dismissal from the military. He subsequently moved to New York where he opened a private practice entirely devoted to neurology, became a founding member of the American Neurological Association, became a professor of nervous and mental diseases at Bellevue Hospital Medical College and in 1871 published A Treatise on Diseases of the Nervous System - the first American textbook of neurology). As patients overflowed the Filbert Street Hospital (16th and Filbert) they were transferred to Christian Street Hospital (9th and Christian) where Mitchell was joined by colleagues George Reed Morehouse and William Williams Keen. Hammond arranged for Mitchell to be transferred to Turner's Lane Hospital (22nd and Oxford) where the team cared for what he referred to as "the awful harvest of Gettysburg." Mitchell later wrote never has such an opportunity for the study of nerve lesions and their results presented itself. A multitude of cases representing almost every conceivable type of obscure nervous disease was sent to us from this department and that of Washington, by surgeons who felt conscious that these forms of disease were rarely amenable to treatment in wards crowded with grave wounds, constantly demanding all the time and care of overworked attendants."

Mitchell's team at Turner's Lane followed a daily routine. Keen lived in the hospital. Mitchell and Morehouse would visit at 7 am. After their professional rounds at their private practices, they would return late in the afternoon to complete detailed exams and note-taking until midnight or early morning hours. They would then walk several miles to their homes. Their experiences resulted in the two monographs - Gunshot Wounds and Other Injuries of Nerves (1864) and Injuries -of Nerves and Their Consequences '(1872). The first to describe phantom limb pain Mitchell wrote, "I found that the great mass of men who had undergone amputations, for many months felt the unusual consciousness that they still had the lost limb. It itched or pained, or was cramped but never felt hot or cold ... I should also add, that nearly every person who has lost an arm above the elbow feels as though the lost member were bent at the elbow, and at times is vividly impressed with the notion that the fingers are strongly flexed." Mitchell first used the terrri causalgia from the Greek kausos {heat) and algos (pain) in 1867. He wrote, Perhaps few persons: who are not physicians can realize the influence which long-continued and unendurable pain may have upon both body and mind. "Perhaps nothing can better illustrate the extent to which these statements may be true than the cases of burning pain, or as I prefer to term it , causalgia, the most terrible of all the tortures which a nerve wound may inflict." Mitchell also observed, "The tendency is toward atrophy, and the thinned and shining skin, constantly fretted with tiny ulcers, seems at last to fail to shelter sufficiently its included nerve ends. Finally, the centers become over-sensitive, and radiate their state of sensitive wakefulness far and wide."

Mitchell's team at Turner's Lane followed a daily routine. Keen lived in the hospital. Mitchell and Morehouse would visit at 7 am. After their professional rounds at their private practices, they would return late in the afternoon to complete detailed exams and note-taking until midnight or early morning hours. They would then walk several miles to their homes. Their experiences resulted in the two monographs - Gunshot Wounds and Other Injuries of Nerves (1864) and Injuries -of Nerves and Their Consequences '(1872). The first to describe phantom limb pain Mitchell wrote, "I found that the great mass of men who had undergone amputations, for many months felt the unusual consciousness that they still had the lost limb. It itched or pained, or was cramped but never felt hot or cold ... I should also add, that nearly every person who has lost an arm above the elbow feels as though the lost member were bent at the elbow, and at times is vividly impressed with the notion that the fingers are strongly flexed." Mitchell first used the terrri causalgia from the Greek kausos {heat) and algos (pain) in 1867. He wrote, Perhaps few persons: who are not physicians can realize the influence which long-continued and unendurable pain may have upon both body and mind. "Perhaps nothing can better illustrate the extent to which these statements may be true than the cases of burning pain, or as I prefer to term it , causalgia, the most terrible of all the tortures which a nerve wound may inflict." Mitchell also observed, "The tendency is toward atrophy, and the thinned and shining skin, constantly fretted with tiny ulcers, seems at last to fail to shelter sufficiently its included nerve ends. Finally, the centers become over-sensitive, and radiate their state of sensitive wakefulness far and wide."

After Mitchell sold his military contract for $400 he returned to civilian life. Philadelphia had long been a center of scientific inquiry including the American Philosophical Society, the Franklin Institute, the University of Pennsylvania and the Academy of Natural Sciences. In 1863 the chair of physiology at The University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine held by Samuel Jackson became available. By that time Mitchell was one of America's leading physiologists. He campaigned for the professorship at Penn in physiology supported by his scientific colleagues in Boston, Philadelphia and Washington. His friend William Hammond wrote to Joseph Leidy, professor of anatomy at Penn (1853-1891), "I understand Jackson is going to retire and I wish to urge you to do what I know you will, exert all your influence for Mitchell. You know he is a working man and that be as it is now I do not know Mitchell's superior in this country in physiology. He lectures well and is educated, cultured and gentlemanly." Despite the support of his peers, the general board of trustees for the University which included only 3 physicians among the 24 members selected instead Francis Gurney Smith, Jr. the son of a prominent Philadelphia merchant and an active member of the Protestant Episcopal Church. Smith's contribution to experimental physiology was considered modest. Hammond wrote to Mitchell in May 1863, "I am disgusted with everything and can only say that it is an honor to be rejected by such a set of apes." (Another unsuccessful candidate for the position at Penn had been Edouard Brown Sequard who following his rejection accepted the position of professor of physiology and pathology of the nervous system at Harvard from 1864-1866 before returning to Paris).

Weir Mitchell's defeat for the position at the University of Pennsylvania coincided with a shift in his intellectual interests  to diseases of the nervous system which had been sparked by his experiences at the Turner Lane Hospital. Those same experiences inspired Mitchell's first

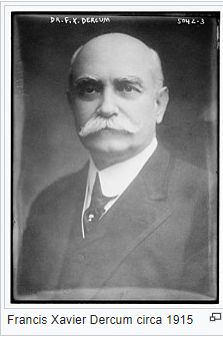

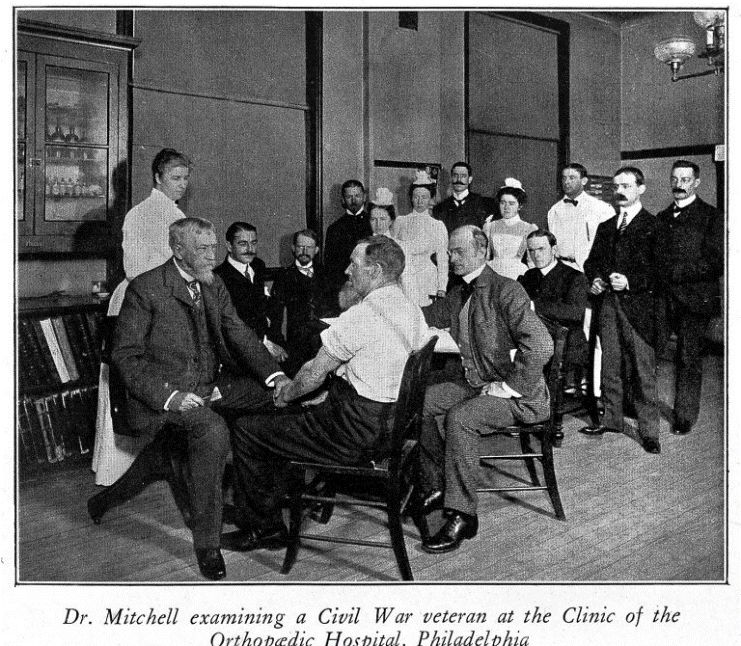

to diseases of the nervous system which had been sparked by his experiences at the Turner Lane Hospital. Those same experiences inspired Mitchell's first  fiction short story "The Strange Case of George Dedlow" which appeared anonymously in the Atlantic Monthly in 1866. Mitchell's second quest for a university professorship met a similar fate when the physiology position of his mentor Robley Dunglison at Jefferson became available in 1868. That same year the Philadelphia Orthopedic Hospital was established. At the time there was no hospital with a neurological ward in Philadelphia. Mitchell wrote to his friend and colleague W.W. Keen, that he "had thirsted for several years for a wider circle of clinical opportunities that a hospital would give for the observation of neurological diseases." Mitchell was elected consultant to the Philadelphia Orthopedic Hospital in 1870 and later that year the neurological infirmary was integrated into the existing hospital. In 1873 the name of the hospital was changed to the Philadelphia Orthopedic Hospital and Infirmary for Nervous Diseases located at 15 S. 9th Street. The by- laws of the institution - the only infirmary for neurological disease in America - was for the benefit of "all persons suffering from bodily deformities or nervous diseases, irrespective of creed or color and particularly intended to assist the indigent in obtaining a permanent cure or relief, providing board and appliances free, or at such cost as can be afforded." In 1871 Mitchell wrote in the annual report of the hospital that it provided neurological care for patients that "often presented to the medical colleges but the professors were entirely unable to give their attention to them without interfering with their imperative duties." While less than 100 patients were admitted in the first year of the Philadelphia Orthopedic Hospital and Infirmary for Nervous Diseases, by the turn of the century over 700 new and 2,600 return visit patients were treated. The variety of neurological diseases seen included locomotor ataxia, chorea, epilepsy, encephalitis, local palsies, hemiplegia, infantile paralysis and adult paralysis, neuralgia and mental disorders. While it was not until 1938 that the hospital merged into the University of Pennsylvania, both the University and Pennsylvania Hospital maintained a close working relationship with the Philadelphia Orthopedic Hospital and Infirmary for Nervous Diseases. Some of the medical staff had formal academic or clinical appointments at the University of Pennsylvania. In addition to patient care, the hospital under Mitchell became a center for advanced neurological postgraduate education. One or two resident physicians were accepted per year for individualized preceptorship at the hospital. The residents lived at the hospital and were only allowed to be absent from the hospital for 6 out of 24 hours except for 2 weeks of summer vacation. Among the residents who trained at the hospital were Charles K. Mills and Francis X. Dercum. Mills had enlisted in1861 at the age of 16 as a private in the Pennsylvania Militia and had fought in the Battle of Antietam. He later became chairman and first professor of Neurology at the University of Pennsylvania. During World War I he taught neurology to medical officers. Dr. Dercum became chief of the Nervous Disease Clinic at the University of Pennsylvania. He also lectured on neurology to medical officers during World War I. When President Woodrow Wilson collapsed in the White House in October 1919, Dr. Dercum was called upon to diagnose him and attended to him within a few hours. Dercum advised Wilson's physician that the president remain in office despite his crippling stroke since with such resignation "the greatest incentive to recovery is gone." He also encouraged Edith Bolling Wilson to stand in as his substitute. (Weir Mitchell had also consulted on President Wilson back in 1912 at the request of the White House physician and predicted that the president would not live out his first term).

fiction short story "The Strange Case of George Dedlow" which appeared anonymously in the Atlantic Monthly in 1866. Mitchell's second quest for a university professorship met a similar fate when the physiology position of his mentor Robley Dunglison at Jefferson became available in 1868. That same year the Philadelphia Orthopedic Hospital was established. At the time there was no hospital with a neurological ward in Philadelphia. Mitchell wrote to his friend and colleague W.W. Keen, that he "had thirsted for several years for a wider circle of clinical opportunities that a hospital would give for the observation of neurological diseases." Mitchell was elected consultant to the Philadelphia Orthopedic Hospital in 1870 and later that year the neurological infirmary was integrated into the existing hospital. In 1873 the name of the hospital was changed to the Philadelphia Orthopedic Hospital and Infirmary for Nervous Diseases located at 15 S. 9th Street. The by- laws of the institution - the only infirmary for neurological disease in America - was for the benefit of "all persons suffering from bodily deformities or nervous diseases, irrespective of creed or color and particularly intended to assist the indigent in obtaining a permanent cure or relief, providing board and appliances free, or at such cost as can be afforded." In 1871 Mitchell wrote in the annual report of the hospital that it provided neurological care for patients that "often presented to the medical colleges but the professors were entirely unable to give their attention to them without interfering with their imperative duties." While less than 100 patients were admitted in the first year of the Philadelphia Orthopedic Hospital and Infirmary for Nervous Diseases, by the turn of the century over 700 new and 2,600 return visit patients were treated. The variety of neurological diseases seen included locomotor ataxia, chorea, epilepsy, encephalitis, local palsies, hemiplegia, infantile paralysis and adult paralysis, neuralgia and mental disorders. While it was not until 1938 that the hospital merged into the University of Pennsylvania, both the University and Pennsylvania Hospital maintained a close working relationship with the Philadelphia Orthopedic Hospital and Infirmary for Nervous Diseases. Some of the medical staff had formal academic or clinical appointments at the University of Pennsylvania. In addition to patient care, the hospital under Mitchell became a center for advanced neurological postgraduate education. One or two resident physicians were accepted per year for individualized preceptorship at the hospital. The residents lived at the hospital and were only allowed to be absent from the hospital for 6 out of 24 hours except for 2 weeks of summer vacation. Among the residents who trained at the hospital were Charles K. Mills and Francis X. Dercum. Mills had enlisted in1861 at the age of 16 as a private in the Pennsylvania Militia and had fought in the Battle of Antietam. He later became chairman and first professor of Neurology at the University of Pennsylvania. During World War I he taught neurology to medical officers. Dr. Dercum became chief of the Nervous Disease Clinic at the University of Pennsylvania. He also lectured on neurology to medical officers during World War I. When President Woodrow Wilson collapsed in the White House in October 1919, Dr. Dercum was called upon to diagnose him and attended to him within a few hours. Dercum advised Wilson's physician that the president remain in office despite his crippling stroke since with such resignation "the greatest incentive to recovery is gone." He also encouraged Edith Bolling Wilson to stand in as his substitute. (Weir Mitchell had also consulted on President Wilson back in 1912 at the request of the White House physician and predicted that the president would not live out his first term).

Mitchell was an avid reader and running out of fiction to read he began to write. In his 50' s Mitchell published 13 novels mainly about society at the time in Philadelphia and the effects of conflicts such as the Civil War and the American and French revolutions on civilian life. Following the death of his first wife, Mitchell married Mary Cadwalader from one of Philadelphia's most prestigious families in 1875. This ·propelled him to one of the city's highest social circles and he became a trustee of the University of Pennsylvania the following year. He served as trustee of the University for 35 years but held the position of professor for only 5 minutes when he was voted the title while briefly absent from a meeting. He promptly resigned when he returned to the room.

Weir Mitchell played a pivotal role in recruiting William Osler to Penn at the same time that Jefferson Medical College was planning to groom him as professor of medicine. Horatio Wood, the first clinical professor of nervous diseases in the newly established department of neurology travelled to Montreal to inquire about Osler. He returned with enthusiastic reports. Mitchell was in England that summer and was asked as a trustee to vet Osler for the Penn position. Osler later described the meeting, "Dr. Mitchell cabled me to meet him in London, as he and his good wife were commissioned to "look me over," particularly with reference to personal habits. Dr. Mitchell said there was only one way in which the breeding of a man suitable for such a position, in such a city as Philadelphia could be tested: give him cherry pie and see how he disposed of the stones. I had read of the trick before, and disposed of them genteelly in my spoon - and got the Chair."

Mitchell also recruited Dr. Osler to join the Philadelphia Orthopedic Hospital and Infirmary for Nervous Diseases soon after his arrival in Philadelphia in 1885 as professor of clinical medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. Osler remained on the staff until his departure for the new hospital and medical school in Baltimore in 1889. Osier's monograph on childhood cerebral palsy was based on cases from the infirmary as was his monograph on the choreas. In addition to developing a new medical school curriculum at Johns Hopkins, Osler published the first edition of The Principles and Practice of Medicine in 1892 including an extensive section on diseases of the nervous system which was based in part on his clinical experiences in Philadelphia.

Mitchell also recruited Dr. Osler to join the Philadelphia Orthopedic Hospital and Infirmary for Nervous Diseases soon after his arrival in Philadelphia in 1885 as professor of clinical medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. Osler remained on the staff until his departure for the new hospital and medical school in Baltimore in 1889. Osier's monograph on childhood cerebral palsy was based on cases from the infirmary as was his monograph on the choreas. In addition to developing a new medical school curriculum at Johns Hopkins, Osler published the first edition of The Principles and Practice of Medicine in 1892 including an extensive section on diseases of the nervous system which was based in part on his clinical experiences in Philadelphia.

Weir Mitchell's association with the Philadelphia Orthopedic Hospital and Infirmary for Nervous Diseases spanned 40 years. In the 1870's his medical research and writings focused increasingly on the rest cure in the treatment of psychiatric disease. His treatment included rest, confinement to bed, dieting, electrotherapy and massage. His method earned him the name "Dr. Diet and Dr. Quiet." Mitchell's reputation as a clinician reached across the ocean. While visiting Paris, a man had fallen ill and had consulted the great neurologist Jean - Martin Charcot. After ascertaining that the man was from Philadelphia, Charcot advised him, "You should consult Weir Mitchell. He is the best man in America for your kind of trouble."

When Weir Mitchell died of influenza in 1914 he was considered one of America's leading physiologists in his early years, the father of American neurology in his middle years and among the most popular of American novelists in his later years. His connection with the University of Pennsylvania began when he entered the college at age 15 and ended as trustee of the University for 35 years.