- Home

- Announcements

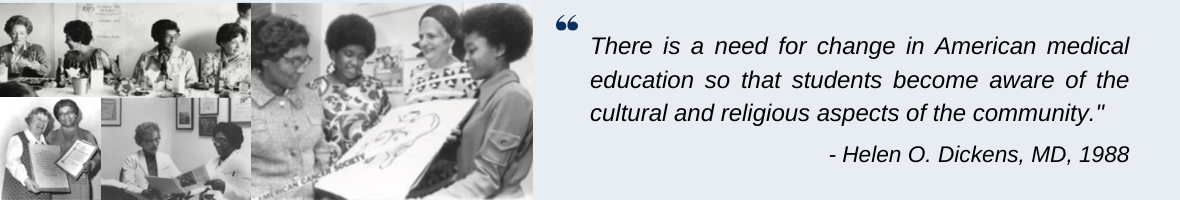

- Helen Octavia Dickens, MD

Helen Octavia Dickens, MD

.png)

She didn't set out to become an activist, but her life's work significantly improved the health - and lives - of women, particularly Black women.

Helen Octavia Dickens, MD was born in Dayton, Ohio, on February 21, 1909. Two landmark events bookended her birth that month: the founding of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and observation of the first National Women's Day in the United States. Despite economic, gender, and racial challenges, Dickens persevered through every step of her medical training and career. With drive and passion, she pioneered initiatives for cancer prevention, family planning, and teen sexual health education, and took them to the underserved Black community. The ripples of her work spread to impact women across the nation.

Dickens achieved many firsts along the way to becoming one of the Perelman School of Medicine's role models and beloved professors of Obstetrics and Gynecology. She also helped bring underrepresented individuals into the medical field and was ahead of her time in imparting lessons of cultural sensitivity to medical students, residents, and colleagues fortunate enough to cross her path, making better doctors out of all.

In the family home in Dayton, Dickens's family set examples for hard work, education, and a spirit to succeed. Her father, formerly enslaved, had taught himself to read and eventually how to read law, but the nature of the times limited him to janitorial work. Her mother found employment as a domestic servant. Both encouraged Helen and her brother to strive toward greater opportunity through education. She recalled attending a "so-called White school," located closer to home than Dayton's Black school, and then attended Crane Junior College in Chicago.

.png)

"I didn't see a barrier to becoming a doctor. It never occurred to me that there were barriers," reflected Dickens in 1988. But medical schools rejected her because she was a woman or because she was African American - and in one case, because she didn't have enough chemistry prerequisites. The University of Illinois School of Medicine accepted her, with a state scholarship funding her education. In 1933, Dickens graduated as one of three women and the only African American woman in her class. She did her internship at Provident Hospital, a Black institution located in Chicago's South Side, and stayed a year for obstetrical training.

In 1935, Dickens came to Philadelphia to work with Virginia Alexander, MD in the Aspiranto Health Home, a six-bed hospital and clinic located in Alexander's North Philadelphia row home. Dickens moved into the home where Alexander's father also resided. The practice primarily served the city's poor Black community, which came to the clinic for general medical care, emergency visits, obstetric and gynecologic care, and parenting classes. Alexander and Dickens made house calls and did home deliveries. During at least one visit to a woman in labor, Dickens had to push a bed to the window for light, as the house did not have electricity.

Alexander charged the same $3.00 whether she saw one patient or a family of six. If the patient couldn't pay, she treated them anyway. Dickens followed her example when, after Dickens's first year at Aspiranto, Alexander left for Yale's School of Public Health, leaving her 27-year-old protégé in charge of the clinic and her father's care.

.png)

Dickens still made times to speak at churches about child welfare and cancer education, work at well-baby clinics, deliver speeches advocating for increased tuberculosis screening in African Americans and participate in the Maternal Mortality Conference of Philadelphia. She worked on the obstetric staff of Frederick Douglass Memorial Hospital and the pediatrics staff at Mercy Hospital - the city's two Black hospitals. They later merged as Mercy-Douglass Hospital, a site that in 2021 was transformed into the PHMC Public Health Campus on Cedar, where Penn Medicine now delivers care through the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania Cedar Avenue.

Seeking more specialized training in OB/GYN, Dickens applied to the University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Medicine. Though cautioned in the interview that she wouldn't be happy in the program - a racial innuendo - Dickens matriculated in 1941 and became the school's first African American woman to earn the Master of Medical Science degree.

Fortuitously, New York City's Harlem Hospital turned down Dickens for a residency first time around, so she returned to Chicago's Provident Hospital where she met surgical resident Purvis Henderson. They married in 1943 and began a long-distance marriage to balance both of their ascending careers - Harlem Hospital subsequently accepted her for three years of residency and he went to Howard University for more training. After treating women at Harlem Hospital for complications related to illegal abortions, Dickens was determined to ensure that all women had access to safe care.

.png)

Dickens returned to Philadelphia where, in 1946, she became the city's first African American woman to receive board certification from the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology. She bought a house at 1512 Oxford Street and started her practice there. Dickens also returned to the Douglass Hospital staff and headed up the Department of Obstetrics at Mercy Hospital. She was pregnant with their first child, Jayne (born in 1947), while Henderson worked in Savannah, Georgia as a pediatric neurosurgeon. The couple later adopted a son, Norman.

Dickens's life was in motion all around: Running a practice while caring for a baby while her husband was in Savannah attending to his own career. In 1948, she took another step, accepting the position of director of OB/GYN at the newly merged Mercy-Douglass Hospital. She established the hospital's OB/GYN residency program, creating training opportunities for Black physicians. Dickens soon joined the courtesy staff of Kensington Hospital, and Woman's Hospital of Philadelphia, as well. "You went where your patients wanted to go," she said, or where they needed to go - such as a prenatal clinic she ran in a North Philadelphia church. Dickens taught at the Medical College of Pennsylvania and Woman's Hospital, rising to department chief of OB/GYN in 1956. She also served on the executive team of Planned Parenthood Association of Philadelphia.

During those years, Dickens made her biggest mark in cancer prevention and education. Cancer had long been perceived primarily as a disease of White women, when in fact, Black women are more likely to die from breast or ovarian cancer. She worked to change that impression and used a community network of Black service organizations including Link, Inc., and her Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc. contacts to reach the city's Black women through seminars held in churches. In a joint effort with the American Cancer Society of Philadelphia, and the National Institutes of Health, Dickens opened a cancer control clinic in Mercy-Douglass Hospital.

.png)

The availability of the Pap smear test in the late 1940s made Dickens a crusader. She lobbied doctors across Pennsylvania to offer the test, and by 1965, had taught 200 Black physicians how to perform it. Dickens also addressed Black women's reluctance to have pelvic exams and pap smears due to fears of sterilization, which came from generations of mistrust in the medical profession from years of experimentation on Black individuals without their consent. She urged the American Cancer Society to create pamphlets and films showing Black women going for Pap smear testing and later having children. And, Dickens took a van to churches and community centers and invited women into the vehicle for free Pap tests.

In 1964, the University acquired Woman's Hospital of Pennsylvania. The following year, Dickens became the first African American faculty member in the Department of OB/GYN. Rising from instructor to full professor and associate dean, she mentored medical students and residents, imparting lessons of age-appropriate and culturally competent care.

Dickens delved deeply into family planning, particularly research on teen pregnancy and sexual health issues, areas of critical need in Philadelphia's Black community. In 1967, she founded the Teen Clinic at Penn, which provided counseling and group therapy, educational classes, contraceptive assistance, and prenatal care. What made the Teen Clinic so innovative and effective was the multidisciplinary approach to working with teens as a cohort of peers and the creation of partnerships with schools. The team included a "male outreach worker" to encourage fathers and new husbands to participate. Dickens offered free contraceptives and advice to the young women about completing their education and seeking job opportunities. By 1970, 40 out of 50 teenage girls Dickens had counseled had started using contraceptives. Her efforts and results inspired local schools and health professionals to design preventative health programs and educational materials designed to lower the incidence of teen pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections.

In 1969, the medical school named Dickens associate dean of minority affairs (later associate dean for minority admissions). She and her assistant, Karen Hamilton, MD, endeavored to recruit Black, Hispanic, and Native American students, then the American Association of Medical Colleges' definition of under-represented minorities. The enrollment of minority medical students increased from one per year to about 14 to 20 per year.

The University appointed Dickens professor emeritus in 1995. She continued to see patients until age 85. In 1987, the PSOM established the Helen O. Dickens, MD Graduation Award to honor a student who has conscientiously endeavored to increase sensitivity and respect for minority groups, in addition to demonstrating outstanding academic performance and leadership. In 1990, the Department of OB/GYN established the Helen O. Dickens, MD endowed fund to support fellowship activities.

Dickens broke a glass ceiling for Black women in medicine with her many firsts. More importantly, she made lasting contributions to women's health, with an exceptional and much needed impact on the Black community. In her advocacy for Pap smear testing for cervical cancer, Dickens saved lives and addressed racial disparities across generations. Her research into teen pregnancy and sexual health issues resulted in successful strategies to lower the incidence of teen pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases. Her outreach - and her characteristic way of reaching out - helped educate young women to empower themselves and to make decisions to that would offer opportunities for a better, healthier future.

.png)

Penn continues to honor Dickens legacy through programs that eliminate barriers to accessing breast and cervical cancer screenings. The Abramson Cancer Center and Pennsylvania Hospital's Ludmir Clinic provide screenings to thousands of uninsured and underinsured women. When PSOM moved to the Jordan Medical Education Center in 2013, students began to be "housed" in one of four communities, including the Dickens House, named after Helen O. Dickens, MD.

.png)

© Carol Perloff (Historian/Writer), Barbara Schwarzenbach (Graphic Artist), & Eric Weckel (Executive Director, SPO)